The Policy Environment

Introduction

The Overall Policy Environment

Strategies

Policies

Laws and Regulations

Introduction

An analysis of the policy context for your research is vital to the establishment of an effective advocacy strategy. It should cover: the policy environment; the policy system; and the organizations and people involved.

In advocacy research people often concentrate on the issue, without paying sufficient attention to how power operates, how change happens and how it is sustained. Policy systems and processes are often complex, with varied and different points of entry. People are at the heart of policy-making, whether they are targets, messengers, allies or opponents. If you wish to influence policy change, you need to understand how key institutions (or organizations) work, who the decision-makers are, and how decisions can be influenced.

Key elements of policy context analysis include:

- Identifying the policy related causes of animal issues

- Understanding the structure of policymaking bodies

- Understanding formal and informal policy making processes

- Identifying key actors and institutions (or organizations) that make decisions about policy, as well as those who can influence policy makers

- Analyzing the distribution of political power among key actors

- Understanding the social and political context

Opportunities to influence policy-makers can arise at any time, so where there is advocacy capacity, it is recommended that the political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological environments are monitored to keep abreast of emerging issues and the positions of government and other leaders with respect to these issues.

The Overall Policy Environment

The policy environment includes all aspects surrounding policy-making. This would include the broader socio-economic aspects that are analysed in organizational strategy-making. Important sources for research into this broader policy environment – and what are the pressing concerns of the day - include: the media, research institutes, veterinary bodies, donors, business, and civil society.

|

Advocacy Tool |

The policy-making environment is greatly influenced by the country’s broader socio-economic situation. This will be covered in Module 3 on Strategic Planning for Advocacy. But in your research, it is important to remember to always keep an eye on the broader horizon, to ensure that you are ready and open for opportunities that may influence or change regular policy processes and priorities.

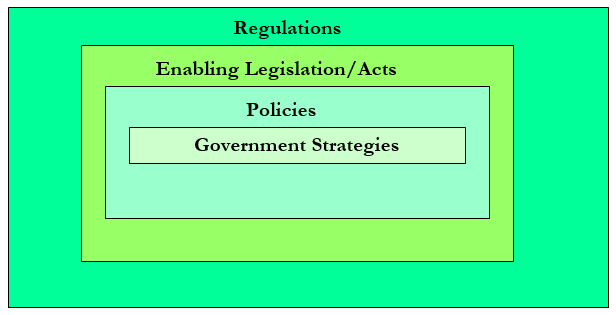

The more narrow governmental policy arena can be depicted diagrammatically as follows:

Key questions to be asked when analyzing the policy environment include:

- What are the animal welfare issues?

- How important are these to both the animals and to society?

- What are the existing strategies, policies and laws that cause or relate to these problems and how are they implemented?

- How could changes in policy help resolve the problems?

- What type of policy change is needed (legislation, proclamation, regulation, legal decision, committee action, institutional practice, or other)?

- What are the financial implications of the proposed policy change?

One aspect of the policy making environment that will have an enormous impact upon your advocacy is the level of openness and transparency. In some open and democratic regimes, it is possible not only to obtain all relevant information through official channels, but also to take part in relevant meetings and consultations. Conversely, in regimes that lack openness and transparency it may be difficult to meet key decision-makers and achieve involvement or consultation (and in some cases even to obtain information through official channels). Advocacy is more likely to be successful in a more democratic and open political system.

Strategies

Investigate the strategies underlying the policies on your issue. If dealing with government, you will find that most governments formulate strategies before taking legislative or administrative action. Strategies will help to identify attitudes, interests and motivations on an issue, as well as future plans.

Policies

Policies form the basis for policy action. They can be international or regional policies (including conventions and agreements), national or organizational.

Research into policies (and policy commitments) can help to identify policy implementation gaps, as well as future plans. Policy research is another important area, as this informs future policy-making. Policy research can be carried out at international, regional, national or local level.

Laws and Regulations

Your research should include any existing laws (acts and regulations) that may affect your issue. Different countries have different legislative systems – see the section below – so these will take different forms.

Once research has identified legislative provisions, it is necessary to go one step further, and to research enforcement.

International standards should be incorporated into national legislation and successfully implemented.

Regional regulations may be directly applicable (as in the case of European Union regulations).

Methodology

Steps in the Research Process

Research Methods and Sources

Organizational Library

Scanning

Meetings and Consultations

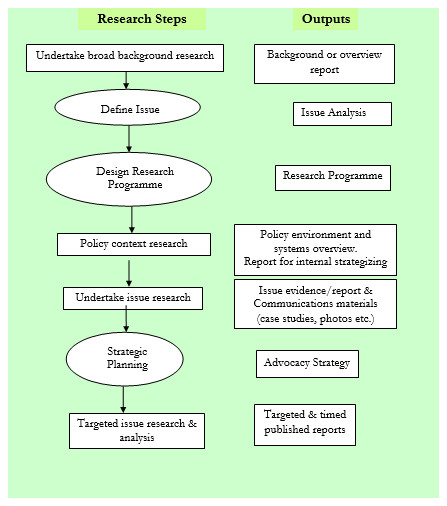

Steps in the Research Process

There may also be additional research needed for strategic analysis

Research Methods and Sources

The first stages of research will include:

- Studies and literature reviews

- Academic or scientific research

- Gathering facts, figures and statistics

After this stage, there are various other research methods available:

- Depth interviews

- Consultations/focus groups/working groups

- Opinion polls

- Surveys and questionnaires

- Computer conferences

- Field visits and investigations

- Case studies

- Pilot projects

There are now many useful sources for research, and using a wide range will add depth, context and interest to your work. Do not restrict your research to the Internet and your local library (however convenient this may seem)! Remember that there are many other organizations out there collecting information (including international organizations, governments, universities and other NGOs) – and many would be only too willing to share this with you. Think of all the bodies with a professional interest in your issue, and find out what research they already have available or are working on.

After desk research, initial fact-finding meetings (e.g. with civil servants working for key policy makers) can help to ascertain key motivations, possibilities, and barriers – which can then be specifically targeted and dealt with in subsequent research.

Avoid going into too much depth before you have made an informed assessment of what is feasible (so as not to waste time).

Also, do not consider your research over as soon as your report has been finished. It pays dividends to keep abreast of your issue throughout your advocacy campaign. If you have the resources, it is helpful to order any relevant publications (such as trade or issue journals). Many organizations organize a press cutting service – where they monitor the media on their issue and send copies of any relevant articles around to interested staff. This helps to update those involved on any changes in policy or public opinion (which can be factored into their advocacy work).

Internet

An enormous amount of information can be found on the Internet these days. Using a search engine, such as Google (see Web Site reference below), you simply enter key words to define your search. If you are inundated with results, then make your keywords more restrictive/accurate. Conversely, if you obtain no results, simply widen your keyword category. When using information found on a Web site in a published document, this should be referenced using the Web Site URL and the date accessed.

|

Tip Remember legitimacy and credibility are necessary for policy influence Double-check and reference your sources. Only use recognized and credible sources (intergovernmental or governmental organizations are excellent sources). A useful ploy is to use your targets’ or your opponents’ information where possible (as they cannot contest this!). Be skeptical when analyzing and citing statistics, as what is reported to government and intergovernmental statisticians and what is actually happening on the ground may be - and often is - very different. Where possible try to verify the statistics you cite by finding data from more than one source. |

Organizational Library

Some animal welfare organizations keep their own reference library. This can be extremely helpful, as it provides quick access to selected books, and relevant reports and other publications. Even smaller organizations can start useful book collections – it is surprising how these build up over time.

Scanning

The broadest form of information gathering is ‘scanning’. It can include all the factual material to be seen on television, read in newspapers and periodicals. To scan effectively the following is needed:

- To identify and order relevant publications

- To ensure a range of publications in order to understand different viewpoints (e.g. different political viewpoints, trade as well as animal welfare etc.)

- A press cutting service/person

- A circulation/notification system

Scanning should be a continuous activity for advocacy organizations.

Need for Focus

As well as different modes of scanning, there are different levels of information gathering ranging from the broader political environment to that related directly to the campaign issue. Tips for advocacy research:

- Target within agreed campaign strategy

- Start wide; decide focus; narrow search

Caution!

In practice any investigation can only use a small fraction of the available information. Warning: information is boundless; scanning can be costly. And don’t forget copyright law, and need to give sources!

Research Support

One good tip is that you may be able to use University students (e.g. veterinary students) to help you with your research. Some may do this free-of-charge, if they can use the results towards their studies/research. This can then also involve the University staff/lecturers, which has the added benefit of adding to their understanding and support.

Meetings and Consultations

Once the available information has been collected, it is helpful to arrange background meetings and fact-finding consultations. These could include potential targets, partners, competitors or any other stakeholders involved in the issue or the fight against it e.g. government, industry, academics/scientists, cultural/religious bodies, professional bodies such as vets, lawyers, biologists etc., and other animal welfare societies/NGOs.

This may lead to a greater understanding of: areas to target and/or avoid; potential strengths and weaknesses; driving factors of the problem; relevant political and legislative factors; potential collaborators and competitors etc.

Advocacy Research and Its Importance

What Sort of Research

Type and Source of Research

Why is Research Important?

What Sort of Research?

In order to persuade policy-makers to change their policies, laws or implementation – be this through direct lobbying or other means such as provoking an official investigation or influencing public opinion – you will need information. To obtain this, you will have to do some research. That could mean anything from combing through piles of documents in the office or a library, to searching the Internet, to taking photos and talking to witnesses. This is all research.

In fact, research is any systematic investigation to discover facts or collect information.

If research is to be useful to policymakers, it will need to be:

General - Providing extensive background information, not just selective cases and anecdotes.

Accessible and Easily Understandable - A body of good evidence, presented in a user-friendly format, and collated and analyzed.

Targeted - Findings are presented in multiple formats, tailored to each audience, with information needs of policy makers (content and format) being taken into account.

Relevant - Appropriate to their area of work, priorities and interests.

Measurable – Incorporating facts, figures and statistics. Timely – Provided at the right time, and using up-to-date information.

Practically Useful – Grounded in reality, and providing practical, feasible and cost effective solutions.

Objective – Gathered from objective sources, without unsubstantiated value judgments or emotional arguments.

Accurate - Providing a true and fair representation of the facts.

Credible - Reliable, sourced appropriately, using accepted tools and methods.

Authoritative - Carried out by an organization that policy makers perceive as credible and reliable.

General background information helps to place the issue in context, providing the ‘bigger picture’ against which the local problem can be examined – for example: by providing facts and figures, or researching the international and regional dimensions of a problem (for instance: international animal welfare standards; regional animal welfare conventions or regulations; or a comparison with the situation in other countries).

Research also helps to personalize your issue and build empathy. You can do this by using methods such as undercover investigations showing individual animal suffering involved; case studies; quotations from witnesses; photo or video evidence etc.

Effective research should:

- Focus on a problem that directly affects the welfare of animals

- Be linked to your program work

- Look into the root causes of problems in order to identify workable solutions

- Analyze the policy environment to uncover implementation gaps

- Link local, national, regional & international aspects

- Collect evidence in a systematic way

The key is that evidence is collected in a rigorous and systematic way.

Type and Source of Research

Categories of Research

There are two categories of research:

- Quantitative – statistical techniques, surveys/market research, experimental techniques

- Can be useful to illustrate scale of problem and/or when you want to generalize about an issue or sector (e.g. the views of 'consumers' or 'voters/public'.)

- Qualitative - views, opinions, and beliefs

- Useful for 'softer' aspects, difficult to quantify (e.g. using focus groups)

Data and Its Sources

The difference between data and information is that data is raw, unprocessed whilst information is in an accessible, meaningful form.

Some useful sources are:

- Internet (range of information ever-increasing

- Libraries

- Directories

- National and local agencies

- Databases

- Government information and statistics and other 'public records' (Freedom of information legislation is a great help here)

- Legislation and precedents (e.g. court cases)

- Trade associations/trade journals/trade e-mail lists/conferences

- Other NGOs, including animal welfare societies

- Exhibitions and conferences

- News media

- Opinion Polls

- A national library (or large public library) is probably the widest ranging source of published information

Referencing

Always make sure to reference your research, so readers can check your sources. In general, what you are trying to achieve is that any reader can clearly see the source of your research (and look this up themselves, if they wish to). There are various formats for referencing your research. One of the most widely used systems of referencing is the APA system (created by the American Psychological Association system, but now used internationally).

Why is Research Important?

Research helps you to gain a clear understanding of the causes and effects of animal welfare issues from the perspective of identifying practical and feasible policy solutions that make it possible to build a consensus in favor for change. It is impossible to argue logically and coherently for policy change without the strong understanding of your issue that research provides.

[In some cases, the only solution to prevent severe animal suffering may be a ban on the practice (e.g. abolition of gin traps). In this case, the evidence of the animal suffering must be strong and graphic in order to convince influential stakeholders.]

Research is the foundation for successful advocacy. It is important for both:

- An effective advocacy strategy - by enabling thorough strategic analysis; and

- Successful advocacy work - by providing authoritative and accurate evidence to support advocacy.

Advocacy research can:

- Give your advocacy substance

- Establish your reputation as an expert on the issue

- Provide feasible and workable solutions to your issue

- Provide you with case studies, anecdotes and examples to make your issue 'come alive'

- Provide cost-benefit arguments, including the (often hidden) cost of alternatives and inaction

- Demonstrate public support or public concern

- Help you to analyze your issue from different perspectives

- Help to disprove myths, rumors and false assumptions

- Analyze and provide counter arguments to positions held by stakeholders who may not be sympathetic to your cause

- Provide evidence for your positions

- Explain why previous strategies have or have not worked

- Provide the basis for media and public awareness work

|

Tip: Do not sweep data under the carpet if it does not support your case! Anticipate and unearth the arguments against you and deal with them in your advocacy work and reports. |

It is said that every dollar spent on research is worth ten spent on lobbying. If your research is thorough, it will be easier to develop a winning advocacy strategy.

Advocacy Research and Analysis

Introduction

Advocacy Research and its Importance

Methodology

The Issue

The Policy Environment

The Policy System

People and Organizations

Targeted Research

Investigations

Further Resources

Introduction

This module examines advocacy research and analysis. Research is the solid foundation of effective advocacy, providing both the key to a winning strategy and indisputable facts for influential lobbying. This module examines different aspects of research and analysis, including not only the policy issue, but also the policy environment, systems, and the organizations and people involved. This includes:

- Research methodology

- Issue choice, and tackling problems at the root

- The policy environment

- People, organizations and power

- The effective use of evidence

"An investment in knowledge always pays the best interest" -Ben Franklin

|

Learning objectives:

|

Module 2: Advocacy Strategy Process Notes

See diagram from the Course Module

Stage 1: Vision/Mission

This is about what you are inspired to do. It can difficult when you are doing for an organization with a number of motivated people. So you need to work creatively, drawing on inspiration. Best to keep away from critical assessments in early stages of development…

Stage 2: Setting the Scene

Organizational Analysis

Big ideas, but not enough resources to deliver? Always burned out and short of time? Then do this before environmental analysis (this provides a background ‘reality check’ - otherwise you’ll end up with more ideas that you can’t accomplish!)

See organizational skills and resources analysis of the Course Module (or Tool 13 Advocacy Self Assessment)

Environmental Analysis

Stuck in a rut – always doing the same things (little imagination and/or and seeing no results) - then do this before organizational analysis. It opens you up to new ideas, possibilities and perspectives.

Tool 10 PESTLE (environmental analysis)

Tool 9 Force Field (really important, not just for the environmental analysis – but also so you can decide on where to direct your energies to achieve change).

OK. So now you know the big picture and your organizations possibilities and limitations! Now look at what others are doing… (So you can see where you fit in to the ‘bigger picture’)

Stage 3: Others and Where You (Could) Fit In

Stakeholder Analysis

Tool 17. Stakeholder Analysis

Tool 6. Allies Opponents Matrix

Tool 18. Johari’s window

Tool 5. Decision and Influence Mapping

Tool 19. Audience Prioritization Matrix

Tool 8. The Venn Diagram

Other Players

Tool 7. Other Player Analysis (in reality, if few AW organizations, you may just decide to ignore them – or to build an alliance – but this tool is useful if the field is crowded)

You don’t want to make unnecessary enemies; or to duplicate the work of others (or do work which others should be doing or are better resourced to do)… Sometimes lobbying others to do what they should be doing is a more effective strategy than simply taking on tasks yourself?

Risk Analysis

Just to make sure you won’t get into too much trouble with your strategy!! [Practical example: an organization (Norway) took court action against battery hen production, and ended up having to pay costs – losing all its funds…].

Strategic Choice

Main decision is what will your organization's 'niche' be?

How do you get from where you are now - to where you want to be?

Strategy workshops with staff and volunteers can be helpful – as they both bring in new ideas and help them to understand the bigger picture… To implement a strategy you will need to bring them along with you… Anything that will assist understanding and decrease resistance!!

Infographic: What is Advocacy?

Why Do Advocacy Work?

Advocacy and Civil Society

Advocacy campaigns by those with less power attempting to influence those with power over them have existed for as long as the power inequalities themselves. They have been documented in many countries for centuries (for example: nationalist and anti-taxation movements in colonized countries; and land’ reform and protectionist movements in post-colonial countries). Advocacy campaigns led by the privileged advocating on behalf of others have included the movements against slavery, racial discrimination, and for women’s rights.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, leading development NGOs became aware that development and emergency work alone was unlikely to produce sustained improvements in the lives of the poor. This lead them to re-examine their strategies, and they started to become increasingly focused on advocacy work. Advocacy work enables them to draw on their program experience to show the impact of existing policies on the poor and marginalized, and to suggest improvements.

The increased democracy, transparency and openness of many governments make advocacy an increasingly effective method of achieving social change. The general trend is for civil society to focus increasingly on advocacy, making government take responsibility for social issues (as opposed to taking over service delivery to ‘fill the gaps’). There are an increasing number and range of advocacy initiatives, with a greater degree of professionalism – and these are now often supported by private foundations (like the Ford Foundation), bilateral donor countries and international donors (such as the World Bank, which has established a ‘Community Empowerment and Social Inclusion Learning Program’ (CESI)).

Advocacy and the Animal Welfare Movement

The animal welfare movement is also developing its advocacy work. There have been animal rights/welfare demonstrations, and animal welfare lobbying, for many decades. Federations, coalitions and alliances have also been formed, including the World Society for the Protection of Animals and one of its predecessors – the World Federation for the Protection of Animals (WFPA), which was founded way back in 1953. However, the movement has been relatively slow in developing effective strategic advocacy, with integrated research and investigations, networking, campaigning and lobbying.

The first truly international animal welfare campaign was launched by WSPA in 1988. This was its successful ‘No Fur’ campaign, which was led by Wim de Kok (now WAN President). It was adopted by over 50 WSPA member organizations and took the arguments against the wearing of fur to all corners of the globe. One of the reasons for the successful roll-out of the campaign was its appealing campaign materials, which used the image of a baby fox with the message: “Does your mother have a fur coat? His mother lost hers…” The campaign keeps on running. It was recently used in China - in a strategic campaign launched by ACT Asia in the autumn of 2011.

These days many of the leading animal welfare organizations carry out strategic advocacy. But many organizations in ‘developing’ countries and local groups continue to concentrate on compassionate, practical animal welfare work – i.e. service delivery, as opposed to advocacy.

There are, however, strong reasons for developing advocacy work. These include the following:

- Traditional practical/rescue & emergency work alone are unlikely to produce sustained improvements in the lives of animals.

- Advocacy is vital to ensuring that the authorities take responsibility for animal issues, including: policy, legislation and enforcement; education and awareness; research and training; and practical programs to improve the lives of animals.

- Advocacy can change attitudes and political will.

- Advocacy is a key tool for addressing the root causes of animal suffering. Advocacy does not merely deal with the symptoms of animal abuse and neglect, but ensures that the underlying educational and structural causes of suffering are addressed.

- In summary, advocacy can improve both the status and welfare of animals in an enduring way.

We also recognize that advocacy can benefit other aspects of our work including: visibility, recruitment, fundraising etc. It can help animal welfare organisations to be recognized as a serious player in civil society circles and provide greater public exposure.

High Impact NGOs

Research carried out at the USA’s ‘Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship’ confirms that although high impact NGOs may start out through designing great programs on the ground, they eventually realize that they cannot achieve large-scale social change through service delivery alone. So they add policy advocacy to change legislation and acquire government resources.

Other NGOs start out by doing advocacy and later add grassroots programs to ‘supercharge’ their strategy. But, ultimately, all high-impact organizations bridge the divide between service delivery and advocacy. They become good at both. And the more they serve and advocate, the more they achieve impact. The NGO’s grassroots work helps to inform its policy advocacy, making legislation more relevant, and advocacy helps the NGO to achieve its policy and program objectives.

What Type of Advocacy?

Types of Advocacy

There are many different types of advocacy work. These should be carefully considered to ensure that the approach adopted is appropriate to your organisation’s ‘ways of working’, the national strategy and country situation, and the aims of the advocacy campaign. There various ways in which to categorize types of advocacy including:

Geographical

Advocacy can take place at any level – in a particular village, community, district, country, region or globally.

Timing

An advocacy campaign could be ongoing or time-limited (e.g. a specific event or action).

Issue

Advocacy can cover a single-issue, or range of issues. In general it is easier to achieve success if you have some specific and focused objectives.

Approach to Issue

Approaches can vary from abolition to reform. Abolition is when advocacy centers around stopping an unpopular policy, whereas reform is where it seeks incremental change. Abolition is likely to be more confrontational (and publicly critical of the existing ideology), whereas reform is usually viewed as more co-operative and/or practical.

Targets

Advocacy can be directed at a number of targets: government, businesses, groups of people or individuals.

Approach to advocacy targets

This can vary from conflict to engagement. Conflict or ‘adversarial advocacy’ is often associated with ardent abolition or protest movements who document the failures of government or policy makers, criticize them ('mobilizing shame'), and thereby effect change. ‘Programmatic engagement’ is more commonly undertaken by organisations that work with government to deliver services. It involves constructive discussion of policies to effect internal reform and capacity building within existing systems.

Channels or methods used

The channels or methods used can range from direct advocacy (direct dealings with policy makers) to grassroots lobbying (mobilizing the public to make representations to policy makers), and include other intermediate approaches such as the use of networks and coalitions.

Different Approaches to Advocacy

Advocacy that is aimed at changing the policies and practices of institutions has been categorized under the following four approaches:

- Collaborative - working with the policy maker to jointly identify an appropriate solution to a particular problem.

- Rational - persuading the policy maker to change their policies through presenting a rational argument, based on evidence and analysis.

- Political - getting the policy maker to change their policies by building support for your case among other groups who have influence on the policy maker, sometimes including public pressure.

- Judicial - forcing the institution to change its policy or practice by using the legal process to get a judgment of the courts.

A collaborative approach can be very effective if the policy-maker is open to change.

The rational approach can work if policies are made on a rational basis (rather than from political or self-interest motives). However, even when this is not the case, the rational approach is often an essential foundation for other approaches.

The political approach recognizes the different forces acting on policy decisions, and tries to build its own agenda into these forces.

The judicial approach can work when the judicial system is fair and independent, and has the authority and power to enforce its judgments. However, it is confrontational and can be slow, expensive and demand specialist skills.

Effective Advocacy

Advocacy is both a science and an art. From a scientific perspective, there is no universal formula for effective advocacy. However, experience shows that advocacy is most effective when it is well-researched and strategically planned. Successful advocacy networks frame their issue, research the policy environment and audience, set an advocacy aim and measurable objectives, identify sources of support and opposition, develop compelling messages, mobilize necessary funds, and collect data and monitor their plan of action at each step along the way.

Advocacy is also an art. Successful advocates develop a ‘sixth sense’ about opportunities, timing, and people – and harness their knowledge in support of the campaign. This comes with experience, and from paying attention to these aspects.

The 'art' of successful advocacy involves:

- Seeking, recognizing and using opportunities.

- Developing a keen sense of timing.

- Developing an understanding of the people involved in the process - there positions and power bases, and their views and motivations

- Framing and articulating issues in ways that inspire targets and motivate them to take action.

- Becoming a skilled negotiator and consensus builder.

- Looking for opportunities to win modest but strategic policy gains while creating still other opportunities for larger victories

- Developing interpersonal skills.

- Learning how to incorporate creativity, style, and even humor into advocacy (in order to draw attention and support to the cause).

The recipe for successful advocacy will differ from country-to-country – depending on the culture and political environment. In some countries the development of personal contacts is vital. However, this does not negate the need for thorough research and an effective strategy.

Course Glossary

Acronyms

- AW

- Animal Welfare

- CESI

- Community Empowerment and Social Inclusion Learning Program

- CIWF

- Compassion in World Farming

- ECEAE

- European Coalition to End Animal Experiments

- ECFA

- European Coalition for Farm Animals

- EU

- European Union

- FAO

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- FIAPO

- Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organizations

- HSI

- Humane Society International

- IFAW

- International Coalition for Animal Welfare

- IFC

- International Finance Corporation

- IMF

- International Monetary Fund

- INGO

- International NGO

- ISPA

- International Society for the Protection of Animals

- M&E

- Monitoring and Evaluation

- NGO

- Non-Governmental Organization

- OIE

- World Organization for Animal Health

- PAAWA

- Pan African Animal Welfare Alliance

- RSPCA

- Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

- SADC

- Southern African Development Community

- SARAWS

- Southern African Regional Animal Welfare Strategy

- SMART

- Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound (Objectives)

- SWOT

- Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats

- TNCs

- Transnational Corporations

- VSO

- Voluntary Service Overseas

- WAN

- World Animal Net

- WFPA

- World Federation for the Protection of Animals

- WSPA

- World Society for the Protection of Animals

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Advocacy Terms

- Allies

- Groups or individuals who share your policy change aim

- Ask

- The core request of your advocacy campaign

- Audience

- The person selected to receive your message (this could be a direct or indirect target)

- Indirect Target

- Person selected to bear influence on your advocacy target (also known as a secondary target)

- Issue Research

- Research on your advocacy issue

- Messages

- The main points that you want to get across in your advocacy, in support of your ask

- Messenger

- The person chosen to deliver your message(s)

- Monitoring &

Evaluation - Monitoring is ongoing checking (that your advocacy is 'on track', and evaluation is a final assessment

- Opponents

- Groups or individuals who counter or oppose your policy change aim

- Other Players

- Other organizations working in the same field and/or on the same issue (similar organizations)

- Policy Context

Research - Research on the policy environment affecting the issue (including: the policy environment, the policy system, and people and organizations)

- Policy Windows

- Brief periods where there are unusual opportunities for policy change

- Target

- The policymaker selected to be the person to whom your advocacy message is addressed - because they have the best opportunity to make policy change also known as a primary target)

- Transparency

- The openness of the policy system and procedures (to the public and civil society)

Introduction Documents

-

Introduction to Advocacy +

-

Advocacy Analysis Tool Contents +

-

Further Advocacy Resources +

- 1