Joint Advocacy

Working Together

Principles of Partnership Advocacy

Models of Joint Working

Working Together

Effective advocacy is best done in conjunction with other organizations supporting the same aim, as this adds ‘greater voice’ to the issue, expanding and strengthening the advocacy campaign. It also helps to empower members and individuals. Joint working can frequently accomplish goals that the individual members could not accomplish alone.

Joint working can also strengthen the advocacy campaign in practical terms, as partners can bring various resources to the table, and the advocacy can more easily be spread geographically. It also gives the campaign greater political and popular support. However, it is important that joint working is given a practical focus, to avoid the common pitfall of endless talking-shops, with no real results.

Partnerships can involve a range of different organizations, including those outside the usual animal welfare community – as appropriate to the advocacy issue. Research and analysis will inform the choice of partners. These could, for example, include organizations as diverse as: development, environment or health NGOs; NGO networks; NGO training bodies; intergovernmental organizations; national and local governments; influential research institutes; veterinary bodies; consumer organizations etc.

Principles of Partnership Advocacy

There are some key principles and recommendations that apply specifically to advocacy work. These are summarized briefly below:

- Integration: Advocacy should not be seen as something separate to your organization’s program work. Advocacy should be integrated into all program work, including ‘service delivery’ work carried out for government. Every practical animal welfare problem should be analyzed in order to find sustainable policy solutions, and advocacy work introduced to achieve these. Advocacy should be introduced throughout your organization’s planning processes: strategic planning; program planning and review; and your budgeting processes.

- Joint planning/play to strengths: If possible, advocacy should be planned from an early stage with the partners. This would usefully include joint strategic planning and a joint steering group.

- Share visibility: The principle of conducting advocacy with partners implies that the visibility that accrues through the work will be shared. Any reports produced as part of the work should include the logo and contact details of each of the main author organizations. Similarly for any public events (conferences, press releases etc), consideration should be given to how each organization could be profiled or credited. Partnership guidelines should be prepared on the use of photos and video footage for publication and communication.

- Focus on capacity development: Each piece of advocacy should leave partners in a stronger position. Expertise in areas such as: advocacy, media, communications, policy, and organizational development should be utilized and shared throughout, and built upon. Where advocacy campaigns cover a number of countries or regions, local knowledge and risk analysis should be valued and shared.

Models of Joint Working

There are various models of formal collaboration on advocacy campaigns. There is also some confusion about names for these advocacy groupings (especially from country-to-country)!

We find it useful to distinguish three main models of joint working:

- Networks: primarily for information sharing

- Alliances: longer-term strategic partnerships

- Coalitions: usually formed for a single issue or campaign

Networks

Advocacy campaigns can be spread through various networks. It is worth remembering that:

- Internet networks are increasing in use and coverage

- Networks are universal and almost everyone belongs to one or more networks

- Networks may be personal or professional; formal or informal; temporary or ongoing. They may include family members, school friends, colleagues, members of the same religious institution, etc.

- Members of a network have at least one thing in common with other members of that network.

This makes them valuable systems for the spread of advocacy messages, and a useful pool for supporters.

Alliances

The work of animal welfare alliances should include the development of concerted advocacy campaigns, and capacity development for advocacy work. The Pan African Animal Welfare Alliance (PAAWA) has as a core mandate: ‘strengthening the work of its member animal welfare organizations across Africa in advocacy and education/awareness, through leadership development and capacity building, and providing a strong collective voice for animal welfare’.

Coalitions

A ‘coalition’ is the primary model of joint working for an advocacy campaign (and we have used the term here to mean any joint working for advocacy purposes). Coalition members contribute resources, expertise, and connections to an advocacy effort, and bring greater political and popular support.

Coalitions can come in different shapes and sizes including:

- Formal: Members formally join the coalition, pay dues, and are identified as coalition members on letterhead, coalition statements etc.

- Informal: There is no official membership, so members are constantly changing. With membership turnover, the issues and tactics of the coalition may also shift.

- Geographic: The coalition is based on a geographical area. It can be local, national, regional (global South and North) or international.

- Multi or Single Issue

- Permanent or Temporary

Different types of coalitions will attract different organizations

Empowering Advocacy

Advocacy can empower a wide variety of stakeholders and supporters to stand up and speak out for animal welfare, sure of their issue and their ability to contribute to change. Empowerment makes an advocacy campaign more powerful and, ultimately, brings sustainable change.

Make your advocacy work participatory: involving partners, allies and supporters. This will build interest and commitment, ensuring that these individuals and organization have a stake in its continued success.

Empowering advocacy should not only work to address advocacy issues, but also seek to make the structures and systems of decision-making more inclusive; ensuring genuine consultation and involvement with animal welfare interest groups.

Advocacy can strengthen animal welfare organizations and supporters through promoting social organization, forming new leaders, and building capacity. Participatory advocacy can also strengthen networks on the national, regional and international level, building a strong collective voice for the movement.

This requires working with animal welfare networks, organizations and supporters to encourage them to think differently about their power relationships; giving them the courage to confront and change political and societal issues affecting animal welfare.

Networking and Alliances

Introduction

Empowering Advocacy

Joint Advocacy

Advantages and Disadvantages of Working in Coalitions

Forming a Coalition

Managing a Coalition

Supporters and Activists

Further Resources

Introduction

Working together with others can make an advocacy campaign more powerful and bring sustainable change. It can also empower those involved, and build their capacity and reputation.

This module explains different models of joint working; including networks, coalitions and alliances. It considers the advantages and disadvantages of working in coalitions/alliances, and provides advice on forming and managing these. Some best practice examples of animal welfare coalitions and alliances will be examined and analyzed. The module includes ways in which joint working can be effectively planned and developed in order to avoid common pitfalls and achieve successful and fruitful advocacy relationships.

It also looks at the involvement of supporters and activists, and how this can be effectively managed.

|

Learning objectives:

|

Module 3: Top Tips

- Build a thorough understanding of both your issue and the policy context (including ways in which social change for animals is achieved in your social and political context – see Module 1)

- Place your issue in context (e.g. using facts and figures, or researching the international and regional dimensions - such as World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) international standards etc.)

- Ensure that your research is credible, accessible and easily understandable

- Identify the causes and solutions for your policy issue, and then build political support around your solutions

- Build understanding of key decision-makers – their interests, motivations and power bases

- Identify the key targets of your advocacy, and then work out how to influence them (for example, through secondary targets)

- Use strategic analysis to determine the target audience for your research reports, then ensure they are tailored to influence this audience (in terms of content, presentation and timing)

Further Resources

Websites

The Web Centre for Social Research Methods

Data Centre – Campaign Research

FREE Resources for Methods in Evaluation and Social Research

Books

Research Methods for Business Students: AND Research Navigator Access Card

Mark N.K. Saunders

Publisher: FT Prentice Hall

ISBN: 1405813970

Research Methods for Managers

John Gill, Phil Johnson

Publisher: Sage Publications Ltd

ISBN: 0761940022

Management Research: An Introduction (Sage Series in Management Research)

Mark Easterby-Smith, Richard Thorpe

Publisher: Sage Publications Ltd

ISBN: 0761972854

Doing Research in Business and Management: An Introduction to Process and Method

Dan Remenyi, Brian Williams, Arthur Money, Ethne Swartz

Publisher: Sage Publications Ltd

ISBN: 0761959505

Investigations

Introduction

Purpose of a Specific Investigation

Investigation Problems

Investigation Skills

Research

Planning

Distribution of Reports/Video

Annexes

Annex 1 - Shooting Principles and Techniques

Annex 2 - Covert Investigations

Annex 3 - Equipment

Annex 4 - Evidence

Annex 5 - Investigations Template

Introduction

Investigations are vital to record exactly what is happening in the places where animals are suffering and being abused. Investigations are the ultimate witness to this abuse. They can be used in a variety of way, including media work and consumer awareness and for prosecutions. Many campaigns have been successful through the power of good investigations footage. When shown on television, this can reach millions, and gain support and supporters (including donations).

The main objectives of an investigation are:

- To document, through video/photographic evidence and eyewitness accounts, precisely how farm animals are treated

- To uncover evidence that laws & regulations surrounding farm animal welfare are being broken

- To provide investigative material to fuel campaigns

- To provide investigative material to be used as evidence to lobby for changes in legislation to improve farm animal welfare

Purpose of a Specific Investigation

Investigations can be costly, time consuming and physically & emotionally draining.

Investigations should only be undertaken if there is a specific aim in using the anticipated results.

Investigations should not stand alone, but be part of a coordinated strategy of the particular animal welfare organization.

The strategy should always be established before any investigation takes place.

Investigation Problems

Many campaigns are now based around investigations, yet the approach (even on some that are successful) is often haphazard and casual. Investigations must be an integral part of strategic and operational planning.

Remember the investigative journalist’s tag ‘The news is something that somebody doesn't want you to know’ in planning your investigation.

Each investigation has to be taken as an opportunity not to be squandered. Once you have visited, your cover is blown, and you may not have a second opportunity.

The biggest problems in investigations are caused by poor planning and lack of experience.

Investigation Skills

A good investigation requires a variety of skills:

- Understanding of how the investigation fits into overall campaign strategy

- Filming and photography

- Interrogation/questioning

- Compilation and assessment of data

- Understanding protocols for record keeping

- Familiarity and understanding of subject

- Knowledge and understanding of relevant legislation

- Flexibility and clear headedness

An individual is unlikely to possess all of these skills, so training and development will be necessary.

|

Tip If your organization does not have investigations expertise, consider employing a professional investigation organization. ‘Tracks Investigations’ (link below) includes experienced animal protection investigators. They can either carry out investigations for you, or train your staff. |

Research

Thorough research is vital before an investigation. There is more on this above. The below are of particular importance:

- Animal welfare Legislation

You need to obtain all relevant legislation and codes/rules. The basic premise of any investigation is that: animal protection legislation is not working, or if there isn't any legislation, you should be calling for some! - Identify possible problems for animal welfare.

Armed with all the information, identify specific problems for animal welfare associated with the investigation

|

Tip Take legislation and key documents on the investigation, if possible. |

Planning

Once you have established why you want to investigate, and what you want to investigate, you need to start to plan an investigation.

Elements of good planning include:

- Control center for investigation

- Timescale for investigation

- Budget for investigation

- Personnel for investigation

- Administration for investigation

- Lists and locations that need investigating

- Route and transportation

- Equipment required for investigation

- How to investigate - the tricky part!

How to investigate

Every investigation is unique but the following are key considerations for investigations:

- Cover Stories

- If needed. Can include tourist, agricultural student, arts student, photography student, agricultural journalist etc. Become familiar with your new persona & practice beforehand. - Shooting Principles and Techniques (see Annex 1 below)

- Open or Covert filming? (see Annex 2 below)

- Equipment (See Annex 3 below)

- Evidence (See Annex 4 below)

- Use an Investigations Template (See Annex 5 below)

- Quality - if you have obtained the opportunity to film openly it is a tragic waste to spoil your ingenuity by relaxing and taking poor quality results. See Annex 1 below for advice on shooting principles and techniques.

It is all to easy to get caught up in the emotion of what you are filming, so again practice as much as possible beforehand with the camera you will be using. A good tip is to watch the news programs on TV to see how programs are made up from sequences of different shots. At the end of the day, you might shoot hours of useless film that you have to watch! Never talk to the media or friends about how you conducted undercover investigations, or the equipment you used.

Distribution of Reports/Video

Use and distribute the material gained as part of your overall strategy. Video footage can be used as follows:

- Supplied to local, national and international media

- Used for videos, photographs, publications, news or magazine articles etc.

- Supplied to other animal welfare advocacy organizations to spread the campaign

Annexes

Annex 1: Shooting Principles and Techniques

The following shooting principles and techniques are a simple, but effective guide to the main features of successful investigations:

- Buy/borrow the best available camera/video

- Be familiar with the controls of the camera (and know its limitations)

- Write and memorize a ‘Shot List’ of shots and sequences you require

- Use the automatic settings until you are confident to use the manual overrides (this can take months/years of practice)

- Never set the date option on the video

- Keep the camera steady - golden rule

- Try each shot as a wide shot, then mid, then close up

- Each shot should be held for at least 20 seconds (This is difficult.)

- Try not to zoom in/out - It makes for uneasy viewing

- Try not to pan/tilt unless you have a tripod

- Try not to talk over your footage unless absolutely necessary

- Understand and use lighting

- Use video lights/ high powered torch in dark conditions

- Don’t forget flash

- Keep yourself focused. It's difficult, but essential

- Use good/appropriate film

- Simple filming is good

- Be calm; take your time. More is better than less

- Review and index photos and tapes

Annex 2: Covert Investigations

Covert Systems

Covert investigations follow the same principles as other cameras, but they can be much more difficult! In particular, remember:

- Covert cameras are prone to malfunction

- If you must use a covert camera, practice as much as possible beforehand

- Practice is more important because you are not looking through the viewfinder

- Lens is the size of a pinhead, so light more critical

- These cameras are very wide angle with lot of depth of field, so get close

- Check camera position

- Don’t be lazy and only use covert system

- Do not show off your camera

Undercover Procedures

- Live your cover and stick to cover story

- Identity card required?

- Have structure to questions for building picture

- Who are you talking to - weigh credibility/knowledge

- Always cross check evidence

- Don't believe hearsay - but test it

- Don't gossip

- Make notes as tables

- Keep a diary

- Remember rules of evidence

- Surveillance

- Keep eyes and ears open

- Don't take short cuts

- Safety should come first

- Don’t forget to check privacy and data protection legislation

Annex 3: Equipment

Just some suggestions to consider:

- Maps (road/track)

- Notebook(s)

- Watch(s) with date

- Pens/pencils

- Plug adapter, if another country

- Tape recorder

- Spare tapes

- Binocular, compass, camping equipment for rural investigations

- High powered torch

- Photo or video camera, with necessary attachments/chargers etc. (Could be using hidden video, long range video, or even video cameras that see in the dark)

Don't forget to check all equipment!

Annex 4: Evidence

Documenting evidence

- Record all relevant details including dates and times, detailed descriptions etc.

- Reports should be authoritative and comprehensive

- Have shorter more accessible leaflets too, if public campaign

- Videos for media – broadcast quality, short (max 12 minutes), double sound track (first cut footage back to max 2 hours, and then review with colleagues)

Assessing evidence

- Expect the person to deny everything

- What does your evidence actually prove

- Don't release material until you have proved your point

- Don't simply release material just because you have it

- If investigation unsuccessful, consider repeating

- How best can evidence be used to change the situation for animals: negotiation, prosecution, lobbying, campaigning/media?

Annex 5: Investigations Template

Rationale for Investigations Template

- To develop innovative approaches to providing quality investigations.

- To ensure that investigative material reaches as wide an audience as possible.

- To ensure that the Investigations Unit operates in accordance with advocacy strategy.

- To review and clarify the needs of investigative material by the organization.

- To optimize the resources of the Investigations Unit.

Template

| Project Title | |

| Overall Objective | |

| UK Objective | |

| European Objective | |

| Relevant Reports/Briefings | |

| Other Background Information | |

| Relevant Legislation | |

| Possible Problems for Animal Welfare | |

| Images/Information Desired (Including Format) | |

|

Methods of Investigation |

|

| Timescale for Investigation | |

| Media Collaborations | |

| Investigative Partners | |

| Planned End Use of Investigation Material | |

| Timetable for Release | |

| Report | |

| Investigators Diaries | |

| Video | |

| How to Be Used by: | |

| Media | |

| Information | |

| Fundraising | |

| Political | |

| Campaigning | |

| Language Versions Required |

Targeted Research

Introduction

How to Target

Examples of Targeted Reports from Animal Welfare Organizations

Introduction

When your advocacy issue has been agreed, and the overall research carried out, it is good practice to target your research. To do this, you first need to determine your target audience (or priority target audience). Then your research reports can be tailored in order to have maximum impact on this audience. The process of targeting may also involve further research.

Your preliminary research and analysis will help you to identify the key targets for your advocacy, and how you can best influence them (e.g. through secondary targets), as in Section 6 of this module. Then you can decide whether to produce one report (e.g. if the needs and interests of your targets are sufficiently uniform) or a number of targeted reports in multiple formats (if their needs and interests are very different, but they are all important to your advocacy). This is both a strategic and a cost-benefit decision!

Another reason for preparing targeted reports is when you seek to link your animal welfare issue into another issue of topical concern. This is often useful in arenas (such as development or the environment) where animal welfare is still viewed as a marginal issue.

Similarly, you may use targeted research for specific political forums, or conferences on specific issues.

However, even in such targeted reports never miss the opportunity to stress your primary concern, and to build understanding and acceptance for animal welfare.

How to Target

In targeting, relevant research findings are presented in multiple formats, tailored to each audience, with the information needs of policy makers (content and format) being taken into account.

In targeting, you should always bear in mind the needs and interests of your target audience. This will affect details such as the length, content, language, presentation, and timing of your reports. For example, politicians and busy policy makers are deluged with information, and simply do not have the time to absorb long written materials. In this case, a very brief summary report is a good idea (preferably with a brief and impactful ‘ask’, or ploy to draw the reader in, at the very beginning).

The use of visual or audio-visual materials is also a key consideration. In animal welfare issues, these can add emotional impact to the written word.

Targeted reports can also be used as ‘asks’ or submissions on a topical political issue or legislative review, or to influence international conferences e.g. Summits, such as Rio+20 (Earth Summit follow-up).

Research can also be used for instructional or educational uses (for example, as course materials or within educational resources).

Examples of Targeted Reports from Animal Welfare Organizations

Compassion in World Farming (CIWF)

CIWF publications listed by subject area

In addition to farm animal welfare issues per se, some CIWF reports are targeted to link into other topical issues, such as:

- Animal health and disease

- Environment and sustainability

- Food industry and consumers

- Human health

- Policy and economics

The World Animal Protection (WAP)

WAP reports under their issues of focus

In addition to reports on animal welfare issues, WAP has targeted a number of its reports to other relevant issues. For example, in the factory farming section these include:

- Humane and sustainable farming

- Case study Enhancing rural livelihoods and nutrition through higher welfare poultry production in IndiaFind out why small-scale, humane chicken rearing in India is better for animals, people and the environment.

- Why livestock and humane, sustainable agriculture matter at Rio+20 This leaflet outlines why humane and sustainable agriculture must be considered when we look at the future of food and farming. The rearing and use of animals has a major impact on the environment, society and the global economy, so ensuring their welfare can help alleviate poverty and encourage sustainable development.

- Animals and People First

- Eating our future - the environmental impact of industrial animal agriculture

- Industrial Animal Agriculture - part of the poverty problem

- Industrial Animal Agriculture - the next global health crisis?

- Practical Alternatives to Industrial Animal Farming in Latin America - Case studies from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica

WAP also produces reports in a number of languages.

Also of interest is the WAP report on:

- Model Farm Project

This provides practical examples of how farming in developing countries can improve animal welfare. WAP has partnered the Food Animal Initiative (FAI), which runs model farms providing examples of best practice in sustainable agriculture and animal welfare, which can be replicated.

The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA)

The HSUS and the RSPCA both target animal welfare audiences and the animal care communities in their countries, as well as the usual advocacy/campaigns audiences. They give out advice on practical animal welfare issues, based on best practice. This is useful and practical targeting given the large number of animal welfare organizations in their countries.

HSUS

Issues

Campaigns

Also guidance and advice – for both education and the animal care community

RSPCA

The science group – authoritative science-based reports

All about animals, including animal care

Reports are produced by each of their animal issue teams (companion animals, research animals, wildlife, farm animals)

International Reports

The above include the following:

- Identification methods for cats and dogs (WAP)

- Methods of euthanasia for cats and dogs (WAP

- Shelter design and management guidelines (RSPCA 2006)

- Shelter design and management guidelines - Spanish (RSPCA 2006)

- Operational guidance for dog control staff (RSPCA 2009)

- The Welfare Basis for Euthanasia of Dogs and Cats and Policy Development (ICAM 2011)

- Population control

- Humane dog population management (ICAM 2007)

People and Organizations

Policymakers, Power and Influence

Power

Influence

Policymakers, Power and Influence

People and organizations are at the heart of policy-making. To succeed in influencing policy, it is necessary to understand them and their motivations, and the way in which power and influence work. Successful advocacy involves building and maintaining relationships that enable you to influence policy-making in favor of your issue.

The first step is to identify which institutions and individuals are involved in decision-making. This will include all stakeholders associated with the desired policy change, for example:

- Decision-makers (major powerful players - include international, regional, national as well as local, where relevant)

- Advisors to decision-makers

- Influencers

- Beneficiaries/the disadvantaged affected

- Allies and supporters

- 'Other players' (other actors in the same field)

- Opponents

- Undecided on the issue (or 'swing voters'

Next, research and analysis is needed to uncover:

- Relationships and tensions between the players

- Their agendas and constraints

- Their motivations and interests

- What their priorities are - rational, emotional, and personal

|

Advocacy Tools Tool 5. Decision and Influence Mapping |

Once you know and understand policy-makers and the way they think, you are better able to judge the channel and tone needed to reach them. They will also assist to identify the best targets (and indirect targets) for your advocacy work.

|

Tip Keep a database of organizations and people, and update as new information is received. Remember to include personal information, as well as organizational. This is invaluable in building relationships. |

Power

Power is a measure of a person’s ability to control the environment around them, including the behavior of other people. In historical terms, it has been monopolized by the few, enabling vested interests to succeed. Much of civil society works to reverse this pattern and bring previously excluded groups and causes into arenas of decision-making, while at the same time transforming how power is understood and used.

An understanding of how power operates is vital to successful advocacy. This includes the power sources of the organizations and individuals involved in policy-making and the roles, relationships and balance of power amongst these. You should also analyze your own power sources, and plan how to use and develop these.

|

Charles Handy, in ‘Understanding Organisations’ (1976) said that if you want to change anything, you need first of all to think about your source of power. |

The main sources of power have been categorized (after social psychologists French and Raven) as follows:

- Legitimate Poweris the formal authority that derives from a position (in an organization) and/or title.

- Reward Poweris based on the capacity to provide things that others desire (such as pay increases, recognition, interesting job assignments and promotions).

- Coercive Powercould be considered the flip side of Reward Power. This power is based on your capacity and willingness to produce punishments or unpleasant conditions (such as criticism, poor performance appraisals, reprimands, undesirable work assignments, or dismissal).

- Connection Poweris the power you derive from relationships with other influential, important or competent people (your network).

- Expert Power is based on your skill, knowledge, accomplishments or reputation.

- Charismatic Power (or 'Referent Power')is based on the personal feelings of attraction, or admiration, that others have for you – often derived from charisma.

- Information Poweris based on you having access to information that others do not have, or do not know about, and which they believe is important. [This power base was added subsequent later.]

It is not always easy to assess sources of power, as these are often complex and hidden. But their impact is pervasive, and they have a great impact upon influence and negotiations.

The use of power from different bases has different consequences. In general, the more legitimate the coercion is, the less resistance and attention it will produce. As advocates and researchers, you may find expert power or information power very powerful. Even those with strong power based upon position and resources do not want to be seen as lacking in information and knowledge! Lobbyists will also find charismatic power useful, through building personal relationships and loyalty. Connection power and legitimate power can be derived through networks and other contacts. Whilst reward and coercive power seem less likely, these can be used when considered necessary e.g. through giving positive media coverage or PR to a beneficial policy change (or the converse, which is bad press for policy failures).

It is useful for advocates to be aware of the different types of power that they, their advocacy allies, targets and opponents have, so they can use this knowledge to inform decisions about the best approaches to adopt and ways in which to develop their own power bases.

Influence

Most organizations have limited resources available for undertaking advocacy work, so it is important to focus advocacy efforts on the individuals, groups or organizations that have the greatest capacity to take action to introduce the desired policy change. These are called 'advocacy targets'. Once we have a clear picture of the decision-making system, we will be able to identify our advocacy targets.

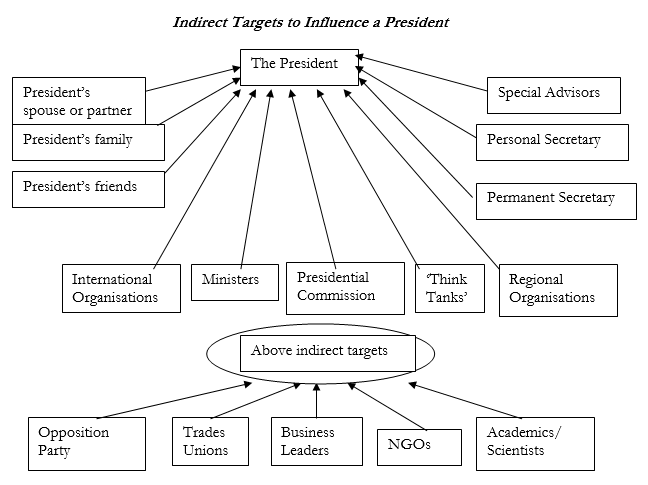

Often, the most obvious advocacy target is not accessible or sympathetic. This means it is necessary to work through others to reach them. This involves working with ‘those who can influence those with influence’ and who have sympathetic views, rather than targeting the decision-maker directly. These are sometimes called 'indirect targets.

This means that in addition to determining targets, you need to assess the most effective ways in which to influence them. This involves research into the position and motivations of each actor, and their sources of advice and influence, in order to decide on the best channels for reaching them on your issue. This approach is known as ‘influence mapping’.

|

Tip Never underestimate the influence of donors and researchers in the policy-making process. Money talks! |

The more information you have about the actors that may influence and affect policy change, the easier it is to devise an effective advocacy strategy.

The following is an example that shows some possible indirect targets that could help to influence a minister.

These indirect targets can also be lobbied in a way that encourages them to lobby other indirect targets (thus making the approach more acceptable to the President (e.g. a NGO lobbies a ‘think tank’ to make approaches to the Permanent Secretary or Special Advisor, who then approaches the President. Or a friend or family member of the President approaches his wife, who then tackles the issue with her husband).

|

Advocacy Tool Tool 5. Decision and Influence Mapping |

The Policy System

Policies

Policymaking Systems

Structures

Processes

Administration and Enforcement

"To change the world, we must first understand it."

Former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan

Policies

Policies form the basis for policy action. They can be international or regional policies (including conventions and agreements), national or organizational.

Research into policies (and policy commitments) can help to identify policy implementation gaps, as well as future plans. Policy research is another important area, as this informs future policy-making. Policy research can be carried out at international, regional, national or local level.

Where national standards of animal welfare are low, the OIE’s international standards on animal welfare are key tools that we can use to hold states accountable in delivering acceptable standards of animal welfare. Advocacy is a key tool to ensure the implementation of these standards, and to hold governments to account.

Policymaking Systems

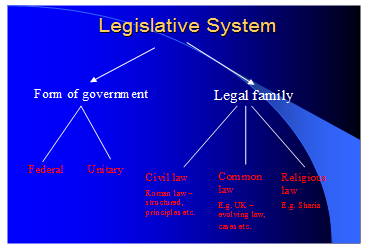

Different countries have different legislative systems, which will impact upon their policy system. Sometimes the provincial or local government might be the target for your advocacy rather than national government. There are also different legal systems (civil law, common law and religious law).

There is sometimes also a written constitution for the country, which is not legislation as such, but provides guiding principles for the country. Constitutional principles have higher standing than legislation (either acts or regulations), and can usually be challenged in a constitutional court.

Some countries are also part of a larger policy-making unit, which can involve policy-making with a number of countries (such as the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union, or the Association of Southeast Asian Nations - ASEAN).

A critical element in the success of any advocacy campaign is a good understanding of the policymaking system of your country. This includes the formal and informal ways in which policies are made at different levels. This analysis helps you to understand the opportunities that exist, including critical points of timing (‘policy windows’).

This knowledge also prevents NGOs from making tactical mistakes that can alienate policy-makers.

In many countries, government and political leaders remain skeptical about including civil society in policy-making, believing that they lack appropriate experience, skills, and knowledge. The way to overcome this perception is to become a skilled and knowledgeable advocate.

"Being aware of the political environment is also very important. There are times when our findings have not been taken seriously, or have been set aside, because the political timing was not right or the research came at an inopportune time in terms of the politics around the research findings."

Mavuto Bamusi of the Malawi Economic Justice Network

The following areas should be covered in the information gathered about the policy-making system:

- The legislative system

- Administrative and enforcement systems

- Policymaking processes

- Agenda setting: including priority of issues

- Timings: including possible policy ‘windows’/opportunities and timing for input/influence (e.g. public reviews or consultation meetings or processes)

- Role of relevant organizations and individuals dealing with your issue

- Role of research and input

- Role of pilot projects

- Relevant conferences/events

- Role and influence of service delivery

- Role/possibility of commissions, working groups or parliamentary committees focusing on your issue (or others which may impact on animal welfare)

Advocacy is not only about changing policies. It is also about changing policy-making structures and processes, to make decision-making more democratic, just and inclusive.

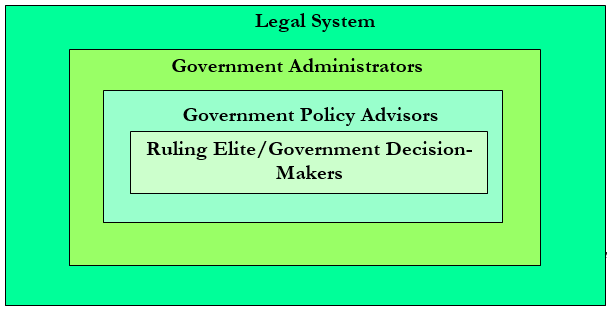

Structures

Legislative structures often follow a system along the following lines:

There can also be broader policy-making structures, some of which feed into this legislative system. These include: international, regional and sub-regional organization and groupings; issue forums; donor forums; civil society networks; business networks; and trade linkages. These all need to be mapped and understood.

Processes

Policy-making processes should also be mapped and understood. This includes the legislative process, which can be quite complex, with various stages for formulating policy, drafting legislation, consultation, and the passage of laws through committees and governmental systems. These processes affect timing, and opportunities for input and influence.

Administration and Enforcement

It is also necessary to map and understand how policies are administered and implemented (and by whom). In many cases, laws are agreed on paper but not enforced, so they are ignored in practice. Factors affecting implementation will include: the nature of the bureaucratic processes (transparency, accountability, participation and corruption), incentives, capacity, and the level of practicality, feasibility and acceptability of the policy.

In this category, it is necessary to include research into factors such as budget allocations; staffing levels and allocation; skill and knowledge levels (training); vehicle and equipment allocations; and monitoring and evaluation mechanisms (i.e. feedback on administration and enforcement, as well as budgetary aspects).

Research should include awareness of policies and practices, as this will impact upon the effectiveness of implementation and enforcement.