Resources

There are so many excellent humane education resources available. So many that it is often difficult to identify the best! We have compiled the list below to help.

Must Look At!

Animal Mosaic (World Animal Protection)

An overview of humane education resources including:

- Suggested curriculum

- Tools for teaching

- Evaluation

- Case studies

Earthkind: A Teachers' Handbook on Humane Education

(Also available on Amazon)

This is an excellent teachers' manual for humane educators.

Really Useful Resources!

The Humane Society of the United States

Resources for parents and educators including lesson plans and worksheets

HEART - Promoting Humane Education

A selection of educational resources for humane education and character education

National Humane Education Society (NHES)

Including lesson plans and educational resources

Association of Professional Humane Educators

Various professional resources, and a list-serve (where professional humane educators can exchange questions and advice). Includes guidelines for humane educators.

TeachKind

Lessons, materials and briefing on issues facing teachers

Institute for Humane Education

Includes graduate programs, online course and a resource center. See also IHE children's books resource.

National Link Coalition

A Resource Center on the Link between Animal Abuse and Human Violence, which includes national and international ‘Link’ coalitions

The Latham Foundation

Promoting humane education, and includes research and resources

International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW)

Educational packs, including teachers’ guides and variety of resources, in a number of different languages

Compassion in World Farming

Wide range of educational resources covering farm animal welfare

Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA)

Interactive educational resource

The Dogs Trust

A selection of teaching resources and fun games

SPANA

Educational resources on working animals

The Humane Education Trust

Includes teachers’ resources designed around the curriculum

Humane Education Resource Guide

The Unlikely Burden

Short stories children’s book aimed to transform perceptions of animals in Africa. (Available in English and Swahili)

Many of the animal protection organizations who have developed these resources will help other animal protection organizations with information and advice on the development and use of educational resources; and allow the use of their templates, artwork and images, to permit adaptation to suit other countries and cultures and/or translation

Puerto Rico

The Puerto Rico Alliance for Companion Animals - PR Animals – has been using creative and inspiring approaches to humane education. At HSUS’s 2014 EXPO, Michelle Cintrón-Matos, their Executive Director, explained the need to engage today’s youngsters with action-centered learning – to compete with their busy lives, including bombardment from TV, films, music, computers and computer games, tablets and mobile ‘phones…

Sitting still and just listening or reading is no longer an effective learning experience.

| Children of Yesterday | Children of today |

|

|

This is why PR-Animals makes sure its programs are creative and interactive.

Creativity is inherent in the approaches they use, which include Shared Photography and Video Production.

Photography and Video are empowering tools to provide students with a creative outlet to voice their concerns and dreams about and for the animals in their communities. This is participatory community photography/video production, and learners participate in defining, taking and constructing a story inspired by the images (as well as directing and acting in the video).

How is it Done?

Students are grouped and divided into sub-groups, and all are given roles:

- Leader

- Camera Custodian

- Photographers/Videographer

And for videos:

- Script writers

- Editor

They are then assigned specific subjects, for example:

- “What is the current situation of animals in Culebra?”

- “What are your dreams for the animals of Culebra?”

Specific tasks and timelines are discussed, for example:

- How long they have to take the pictures/footage?

- How will they construct the stories/narratives?

- How long do they have for writing the video script?

- Who will edit the video?

This is a team exercise, where interaction is part of the process.

[It also teaches the learners valuable team and organizational skills.]

I’ve learned to cede control of the classroom over to the students over time; there is a trust, an understanding and a dedication to an ideal. I simply don’t have to do what I thought I had to do as a beginner teacher: control every conversation and response in the classroom. It’s impossible. Their collective wisdom is much greater than mine and I admit it to the openly.” John Hunter, World Peace Game

What Do You Need?

- Cameras (compact, phone camera, disposable)

- Video (video camera, phone with video camera, compact camera with video capabilities) and computer (Editing Software: iMovie, Movie Maker)

- Cooperative teacher/social worker

- Consent/Releases

- Clear instructions

- Community sharing strategy

- School/community exhibition

- Media – if using the film for television/public service announcements

Potential Partners

- Teachers/Social Workers

- Parents

- Media

- Municipalities/Government

- Private Sector (including for camera donation/sponsorship!)

Before starting - Listen!

- Be prepared

- Look for creative partners

- Help them focus their ideas

- Listen to their voices

- Resist the urge to control

- Be flexible

- Enjoy the gift!

Other creative humane education methods suggested:

- Story writing and story telling

- Creative posters

- Art competitions

Take a Look at Some of PR-Animals' Work:

Video ‘Discover the Heart in Every Animal’

A project by the Puerto Rico Alliance for Companion Animals in collaboration with Fundación para el Capital Social, lead by Dr. Astrid Morales who was certified in the PhotoVoice © methodology

"There are two educations: one should teach us how to make a living and the other how to live." John Adams

Malawi

The Lilongwe Society for the Protection and Care of Animals (LSPCA) was started in 2008 by a dedicated group of Malawian residents, with support and funding from RSPCA International. It is the first and only animal welfare organisation in Malawi and, in addition to its practical animal welfare work, it runs several programmes to improve animal welfare through the provision of veterinary services and education.

LSPCA’s vision is a Malawi where all animals as well as people are treated with care, compassion and respect. They recognise the importance of humane education to the achievement of this vision, saying that: “Humane Education aims to instil a positive attitude towards animals, people and the environment, creating a sense of compassion, responsibility and respect for all living things. Educating children in these values and how to care for their own animals can help to prevent animal cruelty.”

They run an active humane education programme in over 50 public schools across Lilongwe, with the full support of the District Education Department. Their lessons teach children that it is our responsibility to care for animals; and stress the importance of providing food, shelter and veterinary care, and treating animals with respect. They focus on pupils of 10-17 years and visit at least two schools each week. Their lessons are always interactive and along with presentations from their team, work with the children to develop debates, role plays, songs and poems about all aspects of animal care and welfare. Animal welfare is often a new concept for the children and teachers, so they work closely with the teachers to make sure the lessons fit well with the overall curriculum.

The LSPCA has worked with the RSPCA to carry out teacher training, and the provision of teachers’ guides for clubs and lessons facilitation.

Kindness Clubs

The LSPCA also runs Animal Kindness Clubs, which were kindly supported by the National Council of SPCAs from South Africa. These are a popular after school activity. This is how they work:

Head teachers appoint a teacher as the ‘club patron’ and the LSPCA runs workshops to train the teachers in animal welfare values and a range of activities focused on different animal welfare themes. This approach provides for creativity and community-tailored activities, and the teachers and children all input into how the club runs. LSPCA is always on hand to support the teachers and design new activities. They consider that Animal Kindness Clubs are a great way to reach out to the wider community, since all club members become ambassadors for good animal care in their communities. Children often tell the LSPCA that they have shared advice on how to care for their dogs and farm animals with other families in their community. The LSPCA also encourages their secondary school club members to act as guides in the primary school clubs to promote peer-to-peer learning.

Humane Education Exams

The LSPCA even organises Humane Education examinations for the students – and gives awards to those who do extremely well. Humane Education exams are aimed at testing the children’s understanding of animal welfare issues before initiating them into the Animal Kindness Clubs.

Nine schools in Lilongwe sat for Humane Education exams in 2013. 1017 students sat the exam, and 511 passed. They even had one pupil who achieved 100%! This was Gift Kamwendo, who said that he had learned a lot about animal welfare and protection through the humane education programme. He added:

“I wish all schools in the country had humane education classes, I look forward to advancing into the Animal Kindness Clubs so that I can learn a lot more and broaden my understanding about animal welfare.”

Dr. Richard Ssuna, the LSPCA’s Program Director, said:

“Humane Education classes and Animal Kindness Clubs are aimed at promoting compassion towards animals in pupils and instil a sense of responsibility to the well-being of the animals under their care.”

“These classes narrow the very wide knowledge gulf between the correct handling and basic care of animals and the norms in our society. Also we dispel the several traditional myths and beliefs that impact on perceptions held in certain communities about animals.”

He also said that the program aims to reach out to school-going children and orient their thinking, to cause an attitude change in both the individuals and the society in which they live.

South Africa

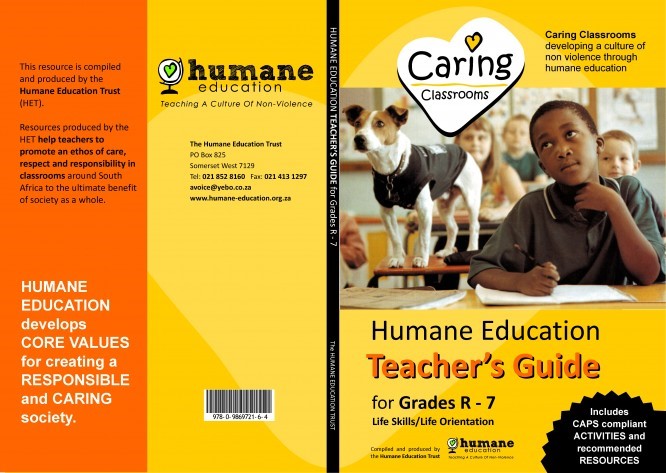

The Humane Education Trust (HET) was founded in 1998 specifically to bring humane education into classrooms throughout South Africa.

In 2000 its founder, Louise van der Merwe, arranged a lecture tour of South Africa by Phil Arkow, a world-renowned expert on the Link between Animal Cruelty and Human Violence. This helped to raise awareness of the importance of humane education in stemming the seeds of conflict and violence before these have taken root. A year later, HET was given the go-ahead by the ‘Safe Schools’ programme of the Western Cape Education Department to pilot a three-month humane education project in 11 schools that had been affected by violence.

The aim of the pilot study was to prove that humane education should be incorporated, as a vital component, in the national curriculum for schools – and it was monitored by a clinical psychologist attached to the Department of Correctional Services.

In his assessment of the pilot project, the psychologist said:

“I think people have lost their sense of connection. We have to leave the world in the hands of people who can care for this world and I cannot think of a better way to start doing this than through humane education.”

Eugene Daniels, the then head of the Western Cape’s Safe Schools Programme, said:

“Our Safe Schools Programme is not only about the elimination of crime and violence in the school environment, it’s about values. You can’t actually address crime and violence unless you look into the hearts and minds of people. In this respect, Humane Education can play a vital role.”

In 2002, the Humane Education Trust became part of the National Department of Education’s National Environmental Education Project (NEEP) programme. NEEP was initiated by the then Minister of Education, Kader Asmal, and aimed to develop resource materials to support environmental and humane education in the Foundation, Intermediate and Senior Phases of the National Curriculum.

In September 2003, 125 educators from across Africa converged on Cape Town for the All-Africa Humane Education Summit. Altogether, 18 African countries attended this historic event including Botswana, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Seychelles, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe and, of course, South Africa. Ronald Swartz, who was head of the Western Cape Education Department at the time, gave the keynote speech at this ground-breaking event. In his speech, he said:

“Anyone who has ever worked on behalf of animal welfare is sure to be asked, sooner or later, ‘why are you so concerned about animals’ sufferings when there are so many humans living in wretchedness? And indeed there is some sense to this question as long as we see ourselves as being essentially separate and different from the natural environment and its kingdoms. But to think like that is to remain stuck in zero-sum thinking, where one thing can benefit only at the expense of another. And there is no need for us to stay trapped in this notion. We are not doomed to any either-or choice between treating animals better and treating humans better. We need to replace that zero-sum notion with the win-win realization that caring about humans and caring about animals are not mutually exclusive: they are two aspects of the same consciousness, and each one reinforces the other… How we treat animals and how we treat each other are two stems that grow from the same root. If there are thorns of neglect, contempt or cruelty on one, we can be sure to find them on the other. The essence of this new approach to the world is a spirit based on respect, and respect is indivisible… We urgently need to help our young people build a better future, a future founded on the very values that Humane Education aims to inculcate.”

In 2011, the final version of the new South African Curriculum Statements for Basic Education for Life Skills in both Foundation and Intermediate Phases, gives multiple allocations to animal care and protection.

Today, HET has a comprehensive selection of readers, documentaries and wall charts that promote the spirit of care and respect for all life. Their resources, many of which have HET is also a full member of the Publishers’ Association of South Africa.

HET also:

- Assists educators in teaching Humane Education through workshops and presentations and by providing accompanying resources to their publications.

- Promotes Humane Education whenever an opportunity arises: At education seminars, in the press, on radio, TV, etc.

Case Studies

South Africa

The Humane Education Trust (HET) was founded in 1998 specifically to bring humane education into classrooms throughout South Africa.

Malawi

The Lilongwe Society for the Protection and Care of Animals (LSPCA) was started in 2008 by a dedicated group of Malawian residents, with support and funding from RSPCA International.

Puerto Rico

The Puerto Rico Alliance for Companion Animals - PR Animals – has been using creative and inspiring approaches to humane education.

Monitoring & Evaluation

Introduction

Designing an M&E System

Introduction

It is vital to monitor and evaluate your humane education program. Monitoring and evaluation - commonly known as ‘M&E’ – is a critical part of the program management and implementation cycle. It allows for adaptive management and improvement through the life of the program to support delivery of program goals and objectives. It also supports reporting and communication of the program outputs and outcomes. This is important for advocacy with educators (the education department and schools/teachers), to promote your organization and its work, and for feedback to funders.

M&E helps us to:

- Learn from experience, and share this learning

- Adapt plans to respond to events

- Improve the effectiveness of future educational work

- Ensure that resources are used in the most effective way possible

- Be accountable to managers, colleagues and funders

- Document evidence of the success of programs, to use for future educational advocacy

Monitoring is a process that tracks the implementation of activities. It checks that we are implementing activities according to our action plan.

Evaluation assesses the results of our project at one point in time (in short-scale projects, this would be on completion – but in longer-scale projects, it could be done periodically).

Historically, the animal protection movement has not been effective at evaluating its part in humane education programs. Whilst there is much anecdotal evidence of the successes and benefits of humane education – not only in terms of improved empathy and compassion, but also in terms of classroom behavior and performance – there is very little rigorous analysis to support this. And this is what is needed to ensure that humane education is taken seriously, and made an integral part of the schools’ curriculum.

Designing a M&E System

The key to designing an effective M&E systems is to work out what you want to achieve in your program (and your program priorities) and:

- Design a monitoring system to ensure that this happens.

- Design an evaluation system that proves that this has happened, and highlights program benefits.

An effective action plan should be the basis of all M&E work.

As the National Association for Humane and Environmental Education states:

“As humane educators we should be concerned not only with our subject matter but also with ensuring that what we do has its desired effect: a positive influence on children's knowledge of, attitudes about, and behavior toward animals.”

The monitoring system for your programs would include aspects such as:

- What is planned is actually taught

- Teachers are effective at teaching (skills, training)

- Teachers actually work for the time/lessons required

- Resources provided are used as expected

- Learners are enjoying the lessons

- Learners are developing as planned in the taught subject(s) (attitudes and behavior)

- Planned by-product effects are taking place (attitudes and behavior)

Monitoring also has an important role to play after humane education has been included in the curriculum (either in its own right, or embedded in another relevant subject area). This is where animal protection organizations can monitor to ensure that it is actually being delivered as agreed.

In many countries, subjects are included in the curriculum and simply not delivered. So monitoring – and follow-up advocacy - is essential for ensuring that humane education is actually delivered. In a similar vein, M&E can continue to document the benefits of humane education, so these can be used in advocacy for more coverage and/or to counter any attempts at subsequently dropping humane education – which remains a threat given packed schools curriculums. Advocacy should remain a vital part of the program to ensure that humane education is rolled out and effectively delivered.

World Animal Protection has some useful information on monitoring and evaluation of animal welfare education programs on its Animal Mosaic site, see ‘How can I tell if it’s working?’

This suggests a few outcomes, but you will probably want to add to these to take account of your own priorities – especially if you are delivering humane education, as opposed to just animal welfare education. In addition, we recommend also factoring in any other desired effects (in terms of learners’ attitudes and/or behavior). This could include aspects of importance to educators and the education department such as: classroom behavior, relationships with other learners and educators, attitudes to learning, critical thinking skills, learning performance etc. Also, where humane education has been weaved into other existing curriculum subjects, then its benefit to these subjects will also need to be factored in (to prove that it has been worthwhile in terms of delivering the curriculum area in question).

World Animal Protection stresses the importance of having a pre-test, and then a corresponding test after the program in order to evaluate its impact – and also of carrying out a control test (to ensure that any changes were actually as a result of the program, and not of any other environmental factors outside of this which affected the learners).

Questionnaires are often used to assess learners’ attitudes before and after the program. If well designed, these can indicate changes in attitude due to the program. But, as World Animal Protection stresses, attitudes can change over time, so need to be re-tested at a later stage to make sure that any changes are maintained.

It is important to remember that such tests can be used for attitudes, but are less successful for evaluating behavioral change – which is best evaluated by peer and/or teacher observation.

Another important point is the need to secure appropriate, permission from the parents of the children being assessed. It is also good practice to ensure that learners’ identities are kept confidential.

The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) has some evaluation instruments on the section of its website for parents and educators.

These were developed for the HSUS by the Western Institute for Research and Evaluation, and can be used in assessing the effectiveness of humane education programs or materials at the kindergarten through sixth-grade levels. Instructions for administering and scoring the tests are included. These assess changes in humane values, so may need to be extended to take account of other program objectives. They may also need to be adapted to suit different cultures.

This web resources also includes bibliographies of research carried out on humane education programs.

Which brings us to a final point: This is the advantages of incorporating academic research into your humane education programs. This not only brings additional academic rigor, but also has the potential to add credence to your claims about the benefits of humane education, and spreads the debate about the importance of humane education into academic circles and beyond.

Methodology

"Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand." Albert Einstein

Background

Moral Discussion

Moral or Values Education

Holistic Class Development

Relevant Educational Theories

So What Methods Work?

Background

The ideal humane education program in the classroom incorporates an exploration of human, animal and environmental rights, to teach children a personal sense of responsibility and a compassionate attitude towards each other, animals and the earth they live on. Children are extremely receptive, their minds are inquiring and active and they have huge supplies of natural enthusiasm. Important messages they receive at school go in deep, yet, this education is the opposite of indoctrination, since the message is not to believe x, y, or z, but to encourage consideration of different issues:

- Thinking about others (including animals) and their needs, feelings, and suffering

- Thinking about the effects of your actions

- Thinking about your world and your place in it.

Well-designed humane education lessons will help learners to develop compassion and empathy and moral values (through lessons using techniques such as role plays, creative dilemmas and discussions).

Ultimately, humane education programs should seeks to inspire each learner to explore, understand and play their unique role in making the world a better place. Each learner will have their own gifts, skills and talents, which they can be helped to recognize and develop. They can also be encouraged to discover their own personal motivations, interests and beliefs, in order to inspire a sense of mission which will lead to right action.

The methods used should be designed to bring inspiration through the drawing out of each learner’s intrinsic wisdom. It is not an instructional (didactic) process, but a facilitative one that provides a supportive atmosphere in which learners feels free to explore their beliefs and express themselves. A range of materials and methods can be used to suit different subjects and learning styles. Both creative and critical thinking abilities need to be used to gain maximum value.

In summary, a well-designed humane education program develops in learners:

- Values and personal ethics (what to do)

- Character (the personality to survive and achieve)

- Strategies and systems (how to do things)

- Critical and creative thinking (new ways of doing things – questioning the ‘status quo’ and ‘thinking out of the box’).

Moral Discussion

The central method used to generate moral development has been moral discussion (Kohlberg). According to Berkowitz (1982), stage change occurred most readily in students who disagreed about the moral solution to a dilemma. An honest approach to moral education will always need to contend with contradiction and controversy (Nucci). However, the conflict needed for moral development has to be constructive not destructive.

WAN Co-Founder Janice Cox has developed a conflict resolution program for the Humane Education Trust of South Africa, which can be used to help learners to enter into non-threatening discussions, using different viewpoints and understanding different perspectives. This Conflict Resolution program includes the following aspects, which are each included in separate booklets (which explain the background to the subject and provide suggested lesson plans for educators):

The course not only prevents conflict, but also develops emotional intelligence. Emotionally intelligent individuals stand out. Their ability to empathize, persevere, control impulses, communicate clearly, make thoughtful decisions, solve problems, and work with others earns friends and success.

This course is a useful adjunct to the introduction of advanced moral discussions in the later stages of humane education.

Moral or Values Education

Moral development moves from ego-centered, through reciprocity (an eye for an eye) and an understanding of shared feelings and interests, towards an understanding of social principles to a final internal feeling based on moral values.

The emphasis of moral or values education is to influence motivation, rather than simply behavior. Behavior has traditionally been influenced by the ‘carrot or the stick’ approach in schools. But this is a temporary fix that does not touch the moral structure (or the moral fiber) of an individual. Humane education programs need to be designed to reach to the core of individual learners, not just to condition their behavior

In the past, educators’ failures to deal with the entirety of the moral person have been obvious but guiltless. Rather it appears that reliance on simplistic theories - and some say arrogance - has been amongst the root causes of the problem (see: The Education of the Complete Moral Person by Marvin W Berkowitz Ph.D.). Below these are a selection of methods that can be used to help learners to differentiate between rules, norms and conventions and universal concerns for justice (fairness and welfare).

Holistic Class Development

Moral and emotional development should not just be something covered in lessons. It should run through the school, and each classroom. To achieve this, classroom democracy and some co-operative classroom goals are needed.

David Johnson (1981) has suggested that successful moral discussion is more likely to take place in classrooms employing co-operative goal structures in a democratic atmosphere than in the traditional classroom environment. There is a considerable body of evidence to support Johnson's claim that co-operative goal structures contribute to moral development.

In addition to being linked to positive social outcomes (such as increased perspective-taking and moral stage, decrease in racial and ethnic stereotyping), co-operative goal structures have been associated with increases in student motivation and academic achievement (Slavin 1980, Slavin et al. 1985).

The peer mediation system contained in the Conflict Resolution resource is democratic and provides co-operative goals. Other aspects of democracy and co-operative goals could be introduced into classrooms to further advance the moral development program.

Relevant Educational Theories

A few relevant educational theories will be examined below. These are all relevant for humane education teaching.

The Learning Cycle

Learning Styles

Learning Preferences

Commuication

Moral Development

Moral Education

The Learning Cycle

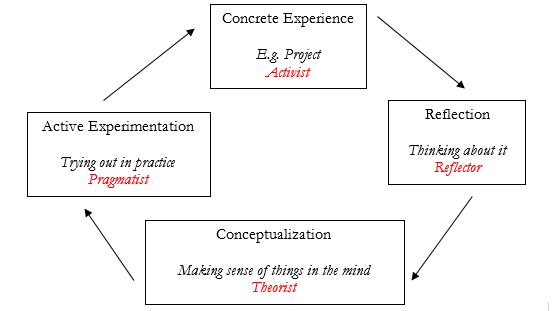

The famous model which explains this is the Kolb Learning Cycle:

|

Example:

|

This model helps to link theory and practice. It can be done by introducing theories, giving learners the opportunity to think about and examine these, and then using them in practical projects.

Alternatively, theories can be explored and debated, and conclusions drawn. Then to solidify the learning, the educator can ask for associated work to be done (e.g. as homework, voluntary work, project assignments etc.) and the results of this ‘active experiment’ brought back into class and explored again.

The process is iterative – learning can be deepened by repeating the process, either at different times or using different lessons to reinforce the same principles.

Learning Styles

Individual learners will have their own learning styles. In reality there are numerous different learning styles. However, Kolb has categorized these into four main styles:

Observers (Reflector)

- These learners like to listen and reflect on events

- They are impartial and observant

- They like to discuss ideas and thoughts

- The pace should allow them time

They like to know how things work, and to have practical examples.

They are not so good at more complex theories and realities, so team well with thinkers.

Thinkers (Theorist)

- These learners like to explore underlying theories

- They have an analytical and conceptual approach

- They thrive on detail and extend discussion

- There is a reduced emphasis on urgency or practical application

They like to research and read theories.

They can be too theoretical – spending too long considering, so team well with a decider.

Deciders (Pragmatist)

- These people like practical experimentation

- They learn best by projects, tasks, etc.

- They value small group discussions

They like to be told the theories and rules and how to apply them.

They prefer clear structure and things that follow the rules.

They are not so good at dealing with messy reality that needs creativity and flexibility, so team well with a doer or an observer.

Doers (Activist)

- These learners like to ‘get stuck in’ to tasks

- Provide concrete experiences for them

- Keep the pace lively and energetic

- They tend to find theory unhelpful

They learn by doing things themselves and learning by their mistakes.

They have an intuitive approach, and are risk takers.

They tend to accept things at face value, so team well with a thinker or an observer.

Learning Preferences

The Neuro-Linguistic Program model (VAK) categorized different learning preferences as follows:

- Visual - Learning through seeing

- Auditory - Learning through listening

- Kinesthetic - Learning through doing, moving or touching

Fleming subsequently expanded on this (in his VARK model), which added the preference of learners towards either reading or writing.

Fleming claimed that visual learners have a preference for seeing (thinking in pictures; valuing visual aids such as overhead slides, diagrams, hand-outs, etc.). Auditory learners prefer to learn through listening (lectures, discussions, tapes, etc.). Tactile/Kinesthetic learners prefer to learn via experience - moving, touching, and doing (active exploration of the world; such as in project work, experiments, etc.).

WSPA Animal Mosaic Tertiary (Teaching) speaks about the theory of multiple intelligences, which differentiates specific (primarily sensory) ‘modalities’, rather than seeing intelligence as dominated by a single general ability. This model was proposed by Howard Gardner in his 1983 book ‘Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences’. Gardner articulated seven criteria for a behavior to be considered an intelligence. These were that the intelligences showed: potential for brain isolation by brain damage, place in evolutionary history, presence of core operations, susceptibility to encoding (symbolic expression), a distinct developmental progression, the existence of savants, prodigies and other exceptional people, and support from experimental psychology and psychometric findings.

Gardner chose eight abilities that he held to meet these criteria: musical–rhythmic, visual–spatial, verbal–linguistic, logical–mathematical, bodily–kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic. He later suggested that existential and moral intelligence may also be worthy of inclusion. Although the distinction between intelligences has been set out in great detail, Gardner opposes the idea of labeling learners to a specific intelligence. Each individual possesses a unique blend of all the intelligences. Gardner firmly maintains that his theory of multiple intelligences should ‘empower learners’, not restrict them to one modality of learning.

Communication

One-Way Communication

One-way communication uses old-fashioned methods. It:

- Imparts facts and knowledge to learners

- Does not expect serious thought, input – or challenges – from learners

- Permits occasional questions only – for clarification

Old didactic (instructional) styles of teaching are out!

Two-way communication often still relies on the educator to:

- Do most of the talking

- Impart information

Although it allows some questions and comments from learners.

Two-way communication is better, but not the best method!

Facilitated or Multi-Way Communication

Here, the educator acts as a facilitator. They guide the process, and ensure that all learners have the opportunity to contribute, and that every contribution is valued. This is the most appropriate method for humane education.

Moral Development

(Piaget's theory)

Piaget observed that the thinking of young children is characterized by egocentrism. That is that young children are unable to simultaneously take into account their own view of things with the perspective of someone else. This egocentrism leads children to project their own thoughts and wishes onto others.

Children begin in a stage of moral reasoning, characterized by a strict adherence to rules and duties, and obedience to authority. Younger children judge against predetermined rules. They value the ‘letter of the law’. For this to work, they need to understand responsibility and outcomes i.e. the imminent sanctions that will occur. This is reinforced by their authority relationship with adults.

Older children are able to determine right from wrong in a wider and more personal sense. They are even able to judge the implications of intent on an action. They value the ‘intent or principle of the law’.

Interactions with other children help to develop this higher moral reasoning – when different rules are traded and a sense of fairness derived (from balancing competing norms and approaches).

Piaget concluded from this work that schools should emphasize cooperative decision-making and problem solving, nurturing moral development by requiring students to work out common rules based on fairness. Thus, Piaget suggested that educators should provide students with opportunities for personal discovery through problem solving, rather than indoctrinating students with norms.

Moral Education

Kohlberg used moral development theories as a basis for rejecting traditional character education methods – which emphasized certain moral virtues and vices, giving learners opportunities to recognize and practice the virtues. He considered that it would prove impossible to determine which virtues were most worthy of espousal. So this approach would, he felt, lead to the educator arbitrarily imposing certain values depending upon their societal, cultural, and personal beliefs. Because of the difficulty of ethical relativity, Kohlberg believed a better approach to affecting moral behavior should focus on stages of moral development.

The goal of moral education, it then follows, is to encourage individuals to develop to the next stage of moral reasoning. This can be achieved through moral dilemmas, and including experiences for learners to act as moral agents in the community.

Teaching practice should work to distinguish morality from convention. Facilitation should be based on the assumption that there are no single, correct answers to ethical dilemmas, but that there is value in holding clear views and acting accordingly. In addition, there is a value of toleration of divergent views. It follows, then, that the teacher's role is one of discussion moderator, with the goal of teaching merely that people hold different values; the teacher does attempt to present his or her views as the ‘right’ views.

So What Methods Work?

"The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be ignited." Plutarch, a follower of Socrates

A really good educator is not one who is standing out the front of the class dictating information to the kids. Enabling educators work out a process that will draw the most from their learners. Then they clearly set out the task and give the learners some tools. They reinforce the belief that the learners are bright and can figure things out – whilst making it clear that they are there to help, if the learners need it.

Learners are the major players in their own learning. They are not the only players – as these will include fellow learners, friends, educators, family, writers etc. To become effective humane educators, teachers need to really get to know their learners as people – on a one on one basis. They should be interested in their home lives, their emotional lives, and their personalities, skills and talents. They should also make an effort to understand the learners’ individual learning styles and learning preferences, and try to use these when giving individual support. Also, make sure that group work is arranged so learners with a range of learning styles can work together and support each other (see Kolb’s learning styles above for some suggestions on teaming learning styles that complement each other). This individual attention may be difficult in today’s large classes, but it is not impossible.

As regards catering for different learning styles, ensure that lessons are designed so as to cater for each different learning style (as every classroom will contain a range). It is tempting for an educator to design lessons according to their own learning style. Be aware of this, and guard against it! It helps to consider your own learning style, so you are aware when you are doing this.

Lessons should be well planned to break tasks down into manageable units, developing a process that unfolds and builds on learning. This is done by analyzing the task, and splitting it into segments. Make sure that the process covers all aspects of the learning cycle. Build lesson plans that include: - theories, thinking time, building concepts, task structure and rules, and active experimentation. This can be done by including homework that gives an opportunity to consider and work on theories, and practical projects and activities through which abstract information (e.g. discussion items) can be tested or developed. Opportunities to test and put learning into practice must be included.

Also, do not forget the need to include multisensory resources and the possibility for multi-sensory outputs or feedback (visual, auditory, kinesthetic).

Where learners are old enough, it is useful to carry out activities in groups. Where possible, this should include self-organization of groups (include self-selection of roles – incorporating identification of skills, talents etc. and making appropriate use of these). Learning how to cooperate in a group is a valuable skill – particularly getting along with others, the art of compromise, and using people in ways that maximize their talents.

Group work should be well organized, with clear explanations of tasks and rules. Give groups control over their environment and the ways in which they get to the required results. Self-regulation of timing and work flow is another useful aspect.

Learning is facilitated when it is based on a reality which the learner recognizes and accepts. This can be achieved through using project-based learning, or using realistic role plays and situational analyses.

With project work, it helps to get the learners excited about a goal. Then fit the learning experience around this. Learners become more enthusiastic when they are able to follow a project of their own choosing, and agree on a common goal.

Other concrete experiences that can be used to help learning would include field trips, voluntary work, drawing and building exercises, classroom productions (arts, film making, musical events, plays etc.).

Creative methods are particularly helpful, because they use the right side of the brain that provokes intuitive responses. This will help to move learners away from learned rules and approaches, which may tend to be reinforced by the factual or theoretical learning that uses the left side of the brain (that deals with information and analysis).

Another tool that can help learners to develop their creative, intuitive responses is meditation. Meditation is a skill that stills the active mind, to create a space for intuition and insights. There are various meditational techniques that can be used, and these can be tried out and the most popular used. The value of meditation is well documented – not only in creating a calmer disposition and assisting intuition, but also in improving concentration in schools. If the conventional school – or parents – are against meditation, then this can be a ‘silent time’ or a ‘peace break’. Here, learners can relax and be quiet. They should be encouraged to still their minds – perhaps assisted by quiet music, a nature visit, or simply listening to their own breathing or heartbeat.

Educators can help children to differentiate between the norms and conventions of their culture and the universal moral concerns for justice (fairness) and welfare. Five educational practices enable teachers to engage in moral education that is neither indoctrinating nor relativistic:

- Moral education should focus on issues of justice, fairness and welfare.

- Moral discussion promotes moral development when the students use ‘transactive’ discussion patterns (negotiations), are at somewhat different moral levels, and are free to disagree about the best solution to a moral dilemma.

- Effective moral education programs are integrated within the curriculum, rather than treated separately as a special program or unit.

- Cooperative goal structures promote both moral and academic growth.

Firm, fair, and flexible classroom management practices and rules contribute to students' moral growth. Teachers should respond to the harmful or unjust consequences of moral transgressions, rather than to broken rules or unfulfilled social expectations (according to Larry Nucci, Director of the Office for Studies in Moral Development and Education and Professor of Education and Psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago).

The central method used to generate moral development is moral discussion. The use of discussion acknowledges that social growth is not simply a process of learning society's rules and values, but a gradual process in which learners actively transform their understanding of morality and social convention through reflection and construction. That is, learners' growth is a function of meaning-making rather than mere compliance with externally imposed values.

Stage change occurs most readily in learners who disagree about the moral solution to a dilemma. Educators can achieve best results by selecting moral dilemmas that are likely to generate disagreement. The educator must permit a variety of opinions and attitudes, and create a classroom atmosphere where learners accept others when their attitudes, beliefs, and values differ from their own. Moral education should assist learners to move through progressively more adequate forms of resolving conflicting claims to justice or human rights.

The constructive exploration of moral dilemmas can be helped by challenging learners’ abilities. They think deeply (and ‘out of the box’) when presented with stretching moral dilemmas. But educators should not be tempted to present learners with materials that are beyond their age level, as this can dishearten and demoralize.

When facilitated effectively, humane education can help to develop ‘multiple intelligences’, which include emotional and interpersonal aspects as well as the cognitive aspects that are developed using more traditional teaching programs. It develops the skills needed to manage emotions, resolve conflict non-violently, and to take just and responsible decisions.

Classroom Management

Moral discussion is more like to take place in classrooms employing co-operative goal structures in a democratic atmosphere than in the traditional classroom environment. Schools should emphasize co-operative decision-making and problem solving, nurturing moral development by requiring students to work out common rules based on fairness. The use of reasoning to respond to transgressions also aids moral development - the morality of justice emerges from coordinating the interactions of autonomous individuals.

Classroom management should be:

- Firm

- Fair

- Flexible (with room for negotiation between educators and learners)

Educators should foster an atmosphere in the classroom that is open, respectful and tolerant. Diversity should be valued, and different abilities stressed and appreciated. Different cultures, religions, and social constructs should be explored and understood in a sensitive and supportive manner. Educators should preach and practice empathy and compassion for all, sprinkled liberally with patience and understanding!

The educator should provide students with opportunities for personal discovery through problem solving, rather than indoctrinating students with their own norms and values. Indeed, educators should work gradually to deconstruct social values and norms, whilst learners are replacing these with their own personal moral values.

Class discussions and negotiations should be encouraged. The educator should create an atmosphere which is open to all viewpoints. No views should be crushed or disregarded – even the more controversial. Create climate of trust and acceptance in class. The class should be a ‘safe haven’ in which contributions are welcomed and valued. Where learners bring forward worrying (or intolerant or antagonistic) viewpoints, ask other learners to comment. Their reflections are likely to provide a greater spur to further reflection.

The way in which feedback is approached is as important as the task itself. Negative criticism should be discouraged (as it is de-motivating). A classroom culture should be developed where appreciative responses are the norm. Concentration on using strengths in teamwork should be followed by recognition of valuable contributions. Group work can build on this, by working consistently towards ‘best fit’ – giving appropriate roles and support within the team. Pleasure and appreciation should be given for shared outcomes. As groups feed back to the complete class, applause and constructive comments should be invited (until these become the norm). Feedback is an art to be learned. Constructive criticism should always be welcomed as a learning opportunity, but the way in which this is worded is important! The educator should guide the learners into ways of giving positive feedback (including through developing empathy with the person receiving feedback).

The educator should encourage the class to care for any learners having problems with their behavior or learning. The ‘buddy’ system can be useful – where an able learner takes a struggling learner under their wing (as a friend and mentor). Always check understanding, so learners are not marginalized or left out of class activities. Fostering the morality of care is an important part of classroom management which builds interconnectedness.

Further Resources on Methodology

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development

Synthesis of Research on Moral Development

Moral Development and Moral Education: An Overview

Learning Styles and Learning Theory

The Curriculum

As we have seen, the ultimate objective for the widespread introduction of humane education is its specific inclusion in the National Curriculum.

The objective of education is not only to provide intellectual development, but also to promote moral/ethical and cultural development. For example, the objective set out in the UK Education Reform Act of 1988 is to:

"Promote spiritual, moral, cultural, mental and physical development of pupils and prepare them for adult life".

Humane education has an essential role to play in providing the moral education desirable in developing children into considerate, responsible adults. Although most governments would acknowledge the importance of a moral dimension to education, few put into practice any real mechanisms to ensure this is actually delivered. One of the most valuable tasks an animal protection organization can perform is to work towards establishing humane education as an integral part of the ongoing school curriculum, convincing governments, school authorities and teachers that humane education is vital to society.

Humane education as part of the curriculum would encompass lessons such as environmental awareness, citizen education and animal protection. An important part of the process of getting humane education formally built into the education system is the development of consolidated course materials covering all of these areas. Commitment to humane education is often a big strength within animal societies and there are excellent and plentiful materials already available in this area to be used as a basis for the animal protection course modules.

The education could readily be developed and presented in a way that enables the children to reach their own conclusions, rather than as indoctrination, offering different viewpoints and philosophies. As Konrad Lorenz, an eminent behaviorist pointed out a vital function of education is “the presentation, to maturing humans, of sufficiently abundant and varied material facts to make it possible for them to perceive all the values associated with the beautiful and the ugly, the good and the bad, the healthy and the sick".

As we have seen, until the aim is realized whereby humane education is given a place of its own in the National Curriculum, there is scope for its introduction through other subjects and cross-curricula themes. However, it should be stressed that humane education is an advanced, all-encompassing discipline (more so than environmental education), so appending it to these lessons is not desirable in the long-term. The best results in this field have been achieved through a dedicated place in the curriculum, with official support for teacher training development and course materials.

As Yehudi Menuhin said:

“Why is compassion not part of our established curriculum, an inherent part of our education? Compassion, awe, wonder, curiosity, exaltation, humility - these are the very foundation of any real civilization, no longer the prerogatives of any one church, but belonging to everyone, every child in every home, in every school".

Strategic advocacy is needed to achieve the inclusion of humane education in the curriculum. There is also more about this in the section on ‘Strategic Approaches’.

A useful resource is World Animal Protection’s Suggested Syllabus (which is for animal welfare education).

This includes: suggested animal protection issues to be covered; suggested educational resources covering for these; and suggestions for linking animal issues into other curriculum subjects.

Which Approach?

Introduction

Existing Channels and Approaches

Strategic Approaches

Introduction

Working for humane education to become an integral part of each child's formal education is fundamental to the long-term strategy of alleviating animal suffering on a grand scale. As we have seen above, it also has important broader societal benefits. So the over-arching aim should be the inclusion of humane education in the schools’ curriculum, and delivery in practice, using the best-available methodology and educational resources.

See here for more about the inclusion of humane education in the curriculum, and ways of achieving this.

See here for more about the best methodologies for delivering human education.

At present, humane education is usually carried out in a piece-meal way, dependent mainly upon the coverage achieved by animal protection groups, or on the inclinations of individual teachers. This may be satisfying and rewarding at the time, but in practice it is difficult to achieve lasting results without sustained and repeated exposure to humane messages and moral reasoning. This is supported by marketing science, which consistently proves that unless any program achieves a high level of exposure, then it is unlikely to achieve its outcomes. Also, this piece-meal approach is not widespread, so its impact is further limited in terms of numbers of students reached.

The reasons why these piecemeal approaches are currently being used are said to include the following:

- Lack of political will/humane education not seen as a priority

- Cultural beliefs/lack of animal protection values

- Lack of human and financial resources

- Difficulty of getting into schools

- HE not in curriculum/curriculum packed

- Long time period between curriculum reviews (e.g. 10 years+ in Kenya)

- Teachers often not willing to do the extra work

- Lack of support from animal protection organizations

- National scale

- Bureaucracy and corruption

These are not necessarily insurmountable challenges - given a real will and passion to succeed, coupled with a skilful strategy!

However, before developing an effective strategy, you need to understand the available channels and approaches to humane education. There is more information on these below.

Finally, we consider strategic approaches; including the targeted use of the advocacy tools that you have at your disposal to achieve your educational objectives.

Existing Channels and Approaches

Approaches to developing humane education vary, as do the channels used. These include:

- Humane Education Specifically in the Curriculum

- Weaving Humane Education into Existing Curriculum Subjects

- Kindness/Animal Welfare Clubs (extra-curricular clubs)

- Non-Formal Humane Education

- Direct Delivery

- Teacher Training/Teacher Trainer Training

- Educational Resource Provision

- Competitions

- Practical Projects and Visits

- Use of Animals

Channels

Humane Education Specifically in the Curriculum

The most successful way of achieving lasting change is to establish a coherent, broad-ranging humane education as part of the national curriculum, preferably in a structure that consolidates social, environmental and animal welfare education. The ideal of a broad-based, all-encompassing humane education is important because this consolidation presents an educational package which is difficult for governments and teaching authorities to ignore (or to subsequently drop) – as it widens its acceptability and coverage. As regards the delivery method, if animal protection groups could be training teachers, or preferably teacher trainers (instead of giving one-off lessons) and producing humane education resources, the educational messages would be spread far more widely.

Weaving Humane Education into Existing Curriculum Subjects

The inclusion of humane education as a separate subject in the schools’ curriculum can be a lengthy process, given the packed educational curriculum of today’s society. However, there are usually many existing subjects in the curriculum where humane education can be interwoven; and specially-adapted educational resources provided, together with teacher support. These vary from country-to-country, so each country will need to examine their own national curriculum to identify which subjects to target.

Firstly, there are particularly relevant subjects such as: Life Skills/Life Orientation, Citizenship, Character/Values Education, Peace Education, Environmental Education, Agriculture/Farming, Biology and Social Studies/Social Science. These are ideal, as a good case can be made for including humane education into such subjects in its own right.

Then, there are other subjects, which are often not considered in this context, but which can effectively be used as vehicles for the introduction of humane education. For example:

- English Language: Using simple animal stories, with humane messages, for a comprehension exercise i.e. studying words and meanings, and then questions and answers.

- English Literature: Using books with humane messages, examining the link between society, culture and humane values etc.

- Art/Design: Presenting humane themes and then drawing, painting, photographing or designing these (e.g. in animal protection leaflets or posters on certain issues).

- Theater: Presenting humane themes and then developing plays about these.

- Media Studies: Examining media portrayal of animal issues and protests – levels of coverage and understanding, target audiences, use of words etc.

- Math: Explaining concepts and then using Math to examine these e.g. Overbreeding of cats (not neutered); comparative costs of humane/organic foods, as opposed to mass produced (examine methods of production and prices/mark-ups) etc.

- IT: Examining web sites of animal protection organizations, both content and design. Consider target audiences and key messages/purposes of the web site etc. Then design a web site for an imaginary animal protection organization (with clear target audiences, purpose and messages).

- Religious Studies: Religious attitudes towards animals.

- Philosophy: Philosophers’ views/perspectives on the treatment of animals.

Some creativity and inspiration is needed to integrate humane education messages into these subjects, but it can be done.

Furthermore, these can all involve an examination of the subject in the learners’ own town/village, before this is included: This makes the concepts real and understandable, and learners can relate to them.

Competitions can also be used as a focus for humane education lessons, particularly in subjects such as Art, Theatre and English (drawing, drama and writing competitions).

The IFAW-sponsored Jungle Theatre Company teaches humane education through theatre in South Africa. Great fun, delivering humane messages and creating lasting impressions.

Kindness/Animal Welfare Clubs (extra-curricular clubs)

Where it is not possible to work directly within the existing curriculum, it may be possible to start an extra-curricular animal protection/kindness club. A school club is a good way to discuss and share knowledge and views about animal issues, educate and inform other students and teachers, and inspire them to get involved. Clubs have the advantage of not being tied to any set curriculum, and can be more action-orientated.

If you want to be a school club, then you will usually be required to meet certain guidelines in order to be officially recognized as a school organization. But if you cannot gain recognition, then you still have the option of being an informal club.

The way in which most ‘Kindness Clubs’ work is by examining the issues, considering the local situation, deciding on priorities, and then taking action. Where many go wrong is by trying to tackle everything – and having no practical focus or results. There are endless animal welfare issues, and just looking and talking about these can have a really depressing effect! But informed action can be quite the reverse – giving the uplifting feeling of having ‘made a difference’.

Jane Goodall’s ‘Roots and Shoots’ program (see below) is an excellent existing club program which works in this way. It is broadly environmental, but many of its clubs are working on animal welfare issues (especially wildlife and companion animals). So you could join an existing club, or set up your own (under the Roots and Shoots program or outside of this). Here are some tips taken from the way in which it works, applied to animal welfare issues:

- Explain the different animal welfare issues (categories/types)

- Investigate the animal welfare problems in your area

- Prioritize the problems

- Call in the 'experts'--organize talks (and/or members' research and presentations)

- Develop a plan for a solution

- Set up a Facebook page (if possible)

- Take action

When working out your action plan, make sure that you use your members' skills, abilities and contacts.

Further Resources:

Roots and Shoots

TEACHKind

Last Chance for Animals

Humane education can be carried out in numerous different ways in addition to the more formal approach used in schools; including non-formal methods such as campaigning. Changes in attitude and behavior have been successfully achieved as a result of powerful campaigns, which are a way of bringing awareness to specific issues relatively quickly, but can lead to sustained change if messages are repeated reinforced over time.

Any method of delivering information, provoking thought and bringing awareness is part of the education process. Public opinion has immeasurable force and can be harnessed in numerous ways:

- Media campaigns

- Television documentaries, advertisements, news items, plays, debates, etc.

- Videos, books, magazines, newspaper articles

- Advertising

- Leaflets, information packs

- Awareness events (exhibitions, open days)

- Demonstrations

- Labelling on products, in supermakarkets, etc.

Animal protection campaigning is an effective method in raising public awareness of animal issues. It can also act as humane education if messages are repeated and reinforced – for example, when messages are (re)presented using many facets or angles (e.g. providing reports, leaflets and other factual materials in addition to more creative/visual mediums, such as media coverage and demonstrations).

Many animal protection societies also use each and every contact with external audiences as an educational opportunity. This is excellent, as it builds interest and understanding of animal welfare issues.

Approaches

Animal protection societies delivering lessons directly is a time-consuming and ultimately unsustainable approach – unless this is in a ‘pilot project’/case study which will be used for advocacy and/or the development of future programs. Good levels of coverage can only be delivered by training additional educators, but this is costly (and recruitment, training and monitoring time-consuming). Even if the funds can be found for wide-scale roll-out, this is ultimately not sustainable (as ongoing funding is seldom possible). With smaller-scale project, the level of coverage remains low, and the option is either to stay at a small number of schools and ensure that messages are reinforced as needed; or move on to new schools (in which case there is no progression). Unless this approach is combined with advocacy and teacher training, there is no significant roll-out.

Teacher Training/Teacher Trainer Training

Teacher training is an excellent way of obtaining ‘multiplier effects’ from your work. The same is even more so of training teachers’ trainers i.e. training those who deliver courses at teachers training colleges. This is especially effective where you have designed targeted programs to tap into the existing schools curriculum. This approach often links with that covered below – the provision of educational resources. Teachers’ workshops need to be well designed, in order to gain ‘buy-in’ and interest from trained teachers; so these benefit from specialist/expert input.

Educational Resource Provision

When providing educational resources for schools and teachers, materials must be adapted to the local situation and educational syllabus.

Various humane education resource materials are available, which may be able to be used or adapted to the local situation. However, in some cases, it is necessary to put in more work (e.g. by commissioning local teachers or – preferably - involving the authorities responsible for curriculum development) to ensure that materials correctly target the national system, circumstances, and audiences.

The production/use of a variety of educational resources (and methods) improves interest and coverage. These can include: teachers’ manuals, students’ workbooks, books with humane messages, poetry, film, Power Point presentations, classroom posters and coloring sheets.

Traditional teachers’ workbooks - loose-leaf, with lesson sheets that can be photocopied for children are particularly useful.

Humane education competitions are an excellent way of encouraging teachers to introduce humane education into their classes, and to awaken the interest and involvement of pupils in humane principles.

Competitions can cover a number of areas: essay writing, letter writing, painting, designing a humane T-shirt, poetry composition and cartoon drawing. It is amazing how creative and inspirational children's entries can be!

The key is to develop creative and imaginative titles for the competition categories. Teachers need to be encouraged to persuade their classes to take part too (perhaps by a teacher award, or kudos?). Prizes are often donated, and media coverage can be achieved (spreading both humane messages, and the organization’s name and reputation).

Visits connected with animal issues can be particularly useful, as they bring educational messages alive. For example, a visit to a local animal shelter; or to different types of farms (e.g. to compare the lives of animals in free-range and intensive farming systems). Wherever possible, a visit to see animals living in the wild, or local nature and beauty spots, are invaluable in helping the learners to (re)connect with nature and animals.

Where schools allow, practical projects which help the community to understand and improve animal welfare issues are ideal for bringing the humane ethic to life; and for spreading awareness of humane principles and the positive benefits of good welfare into the broader community.

Another level of humane education tackles the use of animals either in classrooms (classroom ‘pets’) or in scientific education (as ‘model’ or for dissection etc.). In the first case, some groups try to dissuade against keeping animals in classrooms, whereas others try to improve welfare (such as the RSPCAs). There is now an international movement against the use of animals in scientific education, coordinated by an organization called ‘Interniche’, which supports and resources people and groups seeking to replace the use of animals and press for ‘conscientious objection to experiments on animals in education.

Strategic Approaches

As can be seen, there are many different channels for delivering humane education, and many different approaches. In order to take a strategic approach to your humane education work you need to be aware of these, and to research your own situation thoroughly. Then you need to chart a path towards your ultimate goal (which should be the specific inclusion of humane education in the national curriculum).

Firstly, you need to assess what is the most productive way of working which is currently feasible. Then you need to work to carry this out in the most effective way possible, and in the process to build support for the next ‘rung on the ladder’ towards your ultimate goal.

Build a good ‘case of need’ for humane education, which uses the many arguments available (many of which are examined in this resource) – but tailor to your own country’s particular needs and priority concerns. For example, most of the advocacy work that was successful in obtaining a place in the curriculum for humane education in South Africa was built around the need to tackle the escalating violence and abuse in that society (and its schoolrooms). The Humane Education Trust of South Africa (HET) invited Phil Arkow, an international expert on the link between animal abuse and human violence who had co-authored a book called ‘Child Abuse, Domestic Violence and Animal Abuse: Linking the Circles of Compassion for Prevention and Intervention’, to the country to spread the message about the important role of humane education in building a culture of compassion and non-violence in society. A year later, HET was given the go-ahead by the education department’s ‘Safe Schools Programme’ to pilot a three-month humane education project to prove that humane education should be incorporated into the national curriculum. The pilot project was carried out in 11 schools that had been affected by violence, and was monitored by a clinical psychologist attached to the Department of Correctional Services. It was a resounding success, and humane education was later added to the curriculum.

There is another important point here: The need to involve the education authorities. Not only in your lobbying, but also in your humane education programs (and your progress and success).

Then you will need an effective impact assessment of the value of humane education – see ‘Monitoring and Evaluation’. Anecdotal evidence and learners' and teachers' feedback are important, as well as measurements/more formal assessments

Treat all your educational work as pilot projects – providing feedback on their successes and strengthening the case for humane education to be included in the curriculum. The other real benefit of effective monitoring and evaluation is that this enables you to constantly improve and perfect your programs.

If your country is less then receptive about animal welfare education, then try linking with other organizations (social, nature, environment, peace, values etc.) to provide a broader humane education package. Then you can highlight animal welfare education as an appropriate ‘entry point’ for younger learners, before building greater support and awareness from the education department.

Also, be aware of the need to build public support and awareness – because ultimately subjects will only stay in the curriculum if they matter to people.

Keep checking when your curriculum is due for review. Then work towards this in your pilot projects, and your advocacy. Even if you are not successful on the first occasion, at least the issue will have been raised and aired – and next time around will be recognized and better understood.

Once you have been successful – and humane education is in the curriculum, don’t stop there! Keep on the advocacy, and the PR. Otherwise it will not be perceived as important, and left out in a future review.

Always showcase your humane education programs to parents and the local community – thereby spreading the impact and outreach, and turning these important constituencies into allies.

The Need for Humane Education

Introduction

The 'Link'

Empathy and Compassion

Ethics and Values

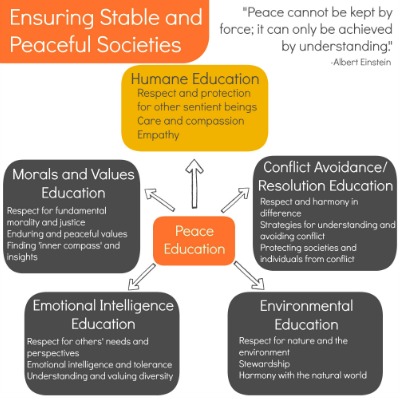

Stable and Peaceful Societies

Introduction

Humane education can play an important role in creating a compassionate and caring society which would take benign responsibility for ourselves, each other, our fellow animals and the earth.

As regards our fellow animals, humane education works at the root causes of human cruelty and abuse of animals. There is now abundant scientific evidence that animals are sentient beings, with the capacity to experience ‘feelings’. They have the ability to enjoy life’s basic gifts as well as the ability to suffer emotionally (as well as physically) through cruel or unkind treatment, deprivation and incarceration. This new understanding of the sentience of animals has huge implications for the way we treat them, the policies and laws we adopt, and the way in which we educate our children.

'Sentience' is the ability to experience consciousness, feelings and perceptions; including the ability to experience pain, suffering and states of wellbeing.

Humane education is the building block of a humane and ethically responsible society. When educators carry out this process using successfully tried and tested methods, what they do for learners is to:

- Help them to develop a personal understanding of ‘who they are’ – recognizing their own special skills, talents, abilities and fostering in them a sense of self-worth.

- Help them to develop a deep feeling for animals, the environment and other people, based on empathy, understanding and respect.

- Help them to develop their own personal beliefs and values, based on wisdom, justice, and compassion.

- Foster a sense of responsibility that makes them want to affirm and to act upon their personal beliefs.

In essence, it sets learners upon a valuable life path, based on firm moral values.

In a well-structured humane education program, younger children are initially introduced to simple animal issues, and the exploration of animal sentience and needs. Then, gradually, learners begin to consider a whole range of ethical issues (animal, human and environmental) using resources and lesson plans designed to generate creative and critical thinking, and to assist each individual in tapping in to their inbuilt ‘moral compass’.

Importantly, humane education has the potential to spur the development of empathy and compassion. Empathy is believed to be the critical element often missing in society today and the underlying reason for callous, neglectful and violent behavior.

There is a well-documented link between childhood cruelty to animals and later criminality, violence and anti-social behavior; and humane education can break this cycle and replace it with one of compassion, empathy and personal responsibility. If we are to build stable and peaceful societies, then humane education must play a vital role in childhood development.

Research has also shown that humane education has an even wider range of positive social and educational outcomes. These even extend to areas such as: bullying, teenage pregnancies, drug-taking, racism, and the persecution of minority groups. It has also been shown to increase school attendance rates, enhance school relationships and behavior, and to improve academic achievement.

Learners who demonstrate respect for others and practice positive interactions, and whose respectful attitudes and productive communication skills are acknowledged and rewarded, are more likely to continue to demonstrate such behavior. Students who feel secure and respected can better apply themselves to learning. Students who are encouraged to understand and live by their own moral compass find it easier to thrive in educational environments and in the wider world.

Humane education should be an essential part of a student’s education as it reduces violence and builds moral character. It is needed to develop an enlightened society that has empathy and respect for life, thus breaking the cycle of violence and abuse. Humane education should be an essential part of a student’s education as it reduces violence and builds moral character. It is needed to develop an enlightened society that has empathy and respect for life, thus breaking the cycle of violence and abuse.

The development of ethics and values in society is something that we ignore at our peril. These must be included in the schools’ curriculum, with humane education at the core.

The 'Link'

When animals are abused and badly treated in a home, there’s a strong chance that people are also being abused in that home by way of child abuse, spouse abuse, and/or abuse of the elderly. When a home is not a safe and caring place for animals it is not a safe and caring place for people either.

Research by psychologists, sociologists and criminologists has proved the link between animal abuse and human abuse. This research over the last 40 years shows that ‘the first strike’ – a person’s first act of violence – is usually aimed at an animal and should be seen as a danger sign for other members of the family. (Source: Humane Society of the United States: First Strike: The Violence Connection.)