Policymakers, Power and Influence

Power

Influence

Policymakers, Power and Influence

People and organizations are at the heart of policy-making. To succeed in influencing policy, it is necessary to understand them and their motivations, and the way in which power and influence work. Successful advocacy involves building and maintaining relationships that enable you to influence policy-making in favor of your issue.

The first step is to identify which institutions and individuals are involved in decision-making. This will include all stakeholders associated with the desired policy change, for example:

- Decision-makers (major powerful players - include international, regional, national as well as local, where relevant)

- Advisors to decision-makers

- Influencers

- Beneficiaries/the disadvantaged affected

- Allies and supporters

- 'Other players' (other actors in the same field)

- Opponents

- Undecided on the issue (or 'swing voters'

Next, research and analysis is needed to uncover:

- Relationships and tensions between the players

- Their agendas and constraints

- Their motivations and interests

- What their priorities are - rational, emotional, and personal

|

Advocacy Tools Tool 5. Decision and Influence Mapping |

Once you know and understand policy-makers and the way they think, you are better able to judge the channel and tone needed to reach them. They will also assist to identify the best targets (and indirect targets) for your advocacy work.

|

Tip Keep a database of organizations and people, and update as new information is received. Remember to include personal information, as well as organizational. This is invaluable in building relationships. |

Power

Power is a measure of a person’s ability to control the environment around them, including the behavior of other people. In historical terms, it has been monopolized by the few, enabling vested interests to succeed. Much of civil society works to reverse this pattern and bring previously excluded groups and causes into arenas of decision-making, while at the same time transforming how power is understood and used.

An understanding of how power operates is vital to successful advocacy. This includes the power sources of the organizations and individuals involved in policy-making and the roles, relationships and balance of power amongst these. You should also analyze your own power sources, and plan how to use and develop these.

|

Charles Handy, in ‘Understanding Organisations’ (1976) said that if you want to change anything, you need first of all to think about your source of power. |

The main sources of power have been categorized (after social psychologists French and Raven) as follows:

- Legitimate Poweris the formal authority that derives from a position (in an organization) and/or title.

- Reward Poweris based on the capacity to provide things that others desire (such as pay increases, recognition, interesting job assignments and promotions).

- Coercive Powercould be considered the flip side of Reward Power. This power is based on your capacity and willingness to produce punishments or unpleasant conditions (such as criticism, poor performance appraisals, reprimands, undesirable work assignments, or dismissal).

- Connection Poweris the power you derive from relationships with other influential, important or competent people (your network).

- Expert Power is based on your skill, knowledge, accomplishments or reputation.

- Charismatic Power (or 'Referent Power')is based on the personal feelings of attraction, or admiration, that others have for you – often derived from charisma.

- Information Poweris based on you having access to information that others do not have, or do not know about, and which they believe is important. [This power base was added subsequent later.]

It is not always easy to assess sources of power, as these are often complex and hidden. But their impact is pervasive, and they have a great impact upon influence and negotiations.

The use of power from different bases has different consequences. In general, the more legitimate the coercion is, the less resistance and attention it will produce. As advocates and researchers, you may find expert power or information power very powerful. Even those with strong power based upon position and resources do not want to be seen as lacking in information and knowledge! Lobbyists will also find charismatic power useful, through building personal relationships and loyalty. Connection power and legitimate power can be derived through networks and other contacts. Whilst reward and coercive power seem less likely, these can be used when considered necessary e.g. through giving positive media coverage or PR to a beneficial policy change (or the converse, which is bad press for policy failures).

It is useful for advocates to be aware of the different types of power that they, their advocacy allies, targets and opponents have, so they can use this knowledge to inform decisions about the best approaches to adopt and ways in which to develop their own power bases.

Influence

Most organizations have limited resources available for undertaking advocacy work, so it is important to focus advocacy efforts on the individuals, groups or organizations that have the greatest capacity to take action to introduce the desired policy change. These are called 'advocacy targets'. Once we have a clear picture of the decision-making system, we will be able to identify our advocacy targets.

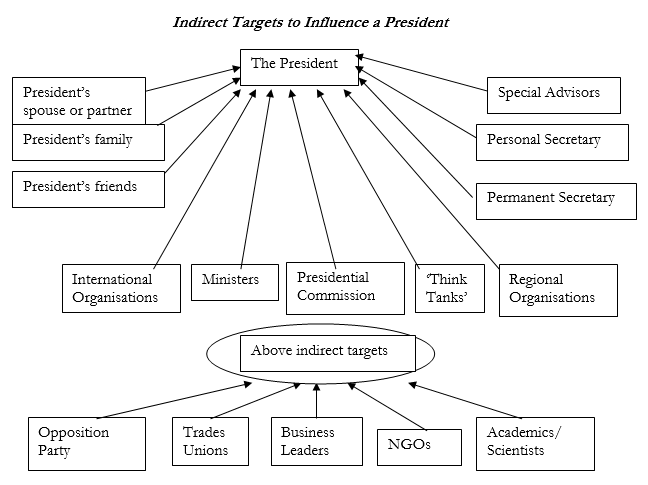

Often, the most obvious advocacy target is not accessible or sympathetic. This means it is necessary to work through others to reach them. This involves working with ‘those who can influence those with influence’ and who have sympathetic views, rather than targeting the decision-maker directly. These are sometimes called 'indirect targets.

This means that in addition to determining targets, you need to assess the most effective ways in which to influence them. This involves research into the position and motivations of each actor, and their sources of advice and influence, in order to decide on the best channels for reaching them on your issue. This approach is known as ‘influence mapping’.

|

Tip Never underestimate the influence of donors and researchers in the policy-making process. Money talks! |

The more information you have about the actors that may influence and affect policy change, the easier it is to devise an effective advocacy strategy.

The following is an example that shows some possible indirect targets that could help to influence a minister.

These indirect targets can also be lobbied in a way that encourages them to lobby other indirect targets (thus making the approach more acceptable to the President (e.g. a NGO lobbies a ‘think tank’ to make approaches to the Permanent Secretary or Special Advisor, who then approaches the President. Or a friend or family member of the President approaches his wife, who then tackles the issue with her husband).

|

Advocacy Tool Tool 5. Decision and Influence Mapping |