"Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand." Albert Einstein

Background

Moral Discussion

Moral or Values Education

Holistic Class Development

Relevant Educational Theories

So What Methods Work?

Background

The ideal humane education program in the classroom incorporates an exploration of human, animal and environmental rights, to teach children a personal sense of responsibility and a compassionate attitude towards each other, animals and the earth they live on. Children are extremely receptive, their minds are inquiring and active and they have huge supplies of natural enthusiasm. Important messages they receive at school go in deep, yet, this education is the opposite of indoctrination, since the message is not to believe x, y, or z, but to encourage consideration of different issues:

- Thinking about others (including animals) and their needs, feelings, and suffering

- Thinking about the effects of your actions

- Thinking about your world and your place in it.

Well-designed humane education lessons will help learners to develop compassion and empathy and moral values (through lessons using techniques such as role plays, creative dilemmas and discussions).

Ultimately, humane education programs should seeks to inspire each learner to explore, understand and play their unique role in making the world a better place. Each learner will have their own gifts, skills and talents, which they can be helped to recognize and develop. They can also be encouraged to discover their own personal motivations, interests and beliefs, in order to inspire a sense of mission which will lead to right action.

The methods used should be designed to bring inspiration through the drawing out of each learner’s intrinsic wisdom. It is not an instructional (didactic) process, but a facilitative one that provides a supportive atmosphere in which learners feels free to explore their beliefs and express themselves. A range of materials and methods can be used to suit different subjects and learning styles. Both creative and critical thinking abilities need to be used to gain maximum value.

In summary, a well-designed humane education program develops in learners:

- Values and personal ethics (what to do)

- Character (the personality to survive and achieve)

- Strategies and systems (how to do things)

- Critical and creative thinking (new ways of doing things – questioning the ‘status quo’ and ‘thinking out of the box’).

Moral Discussion

The central method used to generate moral development has been moral discussion (Kohlberg). According to Berkowitz (1982), stage change occurred most readily in students who disagreed about the moral solution to a dilemma. An honest approach to moral education will always need to contend with contradiction and controversy (Nucci). However, the conflict needed for moral development has to be constructive not destructive.

WAN Co-Founder Janice Cox has developed a conflict resolution program for the Humane Education Trust of South Africa, which can be used to help learners to enter into non-threatening discussions, using different viewpoints and understanding different perspectives. This Conflict Resolution program includes the following aspects, which are each included in separate booklets (which explain the background to the subject and provide suggested lesson plans for educators):

The course not only prevents conflict, but also develops emotional intelligence. Emotionally intelligent individuals stand out. Their ability to empathize, persevere, control impulses, communicate clearly, make thoughtful decisions, solve problems, and work with others earns friends and success.

This course is a useful adjunct to the introduction of advanced moral discussions in the later stages of humane education.

Moral or Values Education

Moral development moves from ego-centered, through reciprocity (an eye for an eye) and an understanding of shared feelings and interests, towards an understanding of social principles to a final internal feeling based on moral values.

The emphasis of moral or values education is to influence motivation, rather than simply behavior. Behavior has traditionally been influenced by the ‘carrot or the stick’ approach in schools. But this is a temporary fix that does not touch the moral structure (or the moral fiber) of an individual. Humane education programs need to be designed to reach to the core of individual learners, not just to condition their behavior

In the past, educators’ failures to deal with the entirety of the moral person have been obvious but guiltless. Rather it appears that reliance on simplistic theories - and some say arrogance - has been amongst the root causes of the problem (see: The Education of the Complete Moral Person by Marvin W Berkowitz Ph.D.). Below these are a selection of methods that can be used to help learners to differentiate between rules, norms and conventions and universal concerns for justice (fairness and welfare).

Holistic Class Development

Moral and emotional development should not just be something covered in lessons. It should run through the school, and each classroom. To achieve this, classroom democracy and some co-operative classroom goals are needed.

David Johnson (1981) has suggested that successful moral discussion is more likely to take place in classrooms employing co-operative goal structures in a democratic atmosphere than in the traditional classroom environment. There is a considerable body of evidence to support Johnson's claim that co-operative goal structures contribute to moral development.

In addition to being linked to positive social outcomes (such as increased perspective-taking and moral stage, decrease in racial and ethnic stereotyping), co-operative goal structures have been associated with increases in student motivation and academic achievement (Slavin 1980, Slavin et al. 1985).

The peer mediation system contained in the Conflict Resolution resource is democratic and provides co-operative goals. Other aspects of democracy and co-operative goals could be introduced into classrooms to further advance the moral development program.

Relevant Educational Theories

A few relevant educational theories will be examined below. These are all relevant for humane education teaching.

The Learning Cycle

Learning Styles

Learning Preferences

Commuication

Moral Development

Moral Education

The Learning Cycle

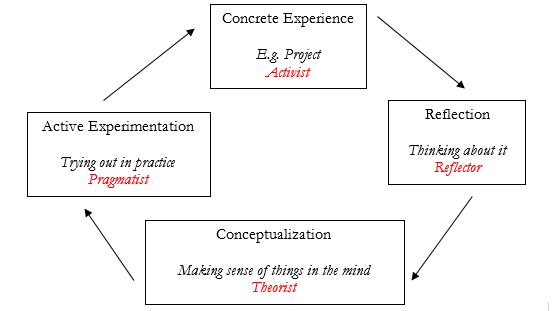

The famous model which explains this is the Kolb Learning Cycle:

|

Example:

|

This model helps to link theory and practice. It can be done by introducing theories, giving learners the opportunity to think about and examine these, and then using them in practical projects.

Alternatively, theories can be explored and debated, and conclusions drawn. Then to solidify the learning, the educator can ask for associated work to be done (e.g. as homework, voluntary work, project assignments etc.) and the results of this ‘active experiment’ brought back into class and explored again.

The process is iterative – learning can be deepened by repeating the process, either at different times or using different lessons to reinforce the same principles.

Learning Styles

Individual learners will have their own learning styles. In reality there are numerous different learning styles. However, Kolb has categorized these into four main styles:

Observers (Reflector)

- These learners like to listen and reflect on events

- They are impartial and observant

- They like to discuss ideas and thoughts

- The pace should allow them time

They like to know how things work, and to have practical examples.

They are not so good at more complex theories and realities, so team well with thinkers.

Thinkers (Theorist)

- These learners like to explore underlying theories

- They have an analytical and conceptual approach

- They thrive on detail and extend discussion

- There is a reduced emphasis on urgency or practical application

They like to research and read theories.

They can be too theoretical – spending too long considering, so team well with a decider.

Deciders (Pragmatist)

- These people like practical experimentation

- They learn best by projects, tasks, etc.

- They value small group discussions

They like to be told the theories and rules and how to apply them.

They prefer clear structure and things that follow the rules.

They are not so good at dealing with messy reality that needs creativity and flexibility, so team well with a doer or an observer.

Doers (Activist)

- These learners like to ‘get stuck in’ to tasks

- Provide concrete experiences for them

- Keep the pace lively and energetic

- They tend to find theory unhelpful

They learn by doing things themselves and learning by their mistakes.

They have an intuitive approach, and are risk takers.

They tend to accept things at face value, so team well with a thinker or an observer.

Learning Preferences

The Neuro-Linguistic Program model (VAK) categorized different learning preferences as follows:

- Visual - Learning through seeing

- Auditory - Learning through listening

- Kinesthetic - Learning through doing, moving or touching

Fleming subsequently expanded on this (in his VARK model), which added the preference of learners towards either reading or writing.

Fleming claimed that visual learners have a preference for seeing (thinking in pictures; valuing visual aids such as overhead slides, diagrams, hand-outs, etc.). Auditory learners prefer to learn through listening (lectures, discussions, tapes, etc.). Tactile/Kinesthetic learners prefer to learn via experience - moving, touching, and doing (active exploration of the world; such as in project work, experiments, etc.).

WSPA Animal Mosaic Tertiary (Teaching) speaks about the theory of multiple intelligences, which differentiates specific (primarily sensory) ‘modalities’, rather than seeing intelligence as dominated by a single general ability. This model was proposed by Howard Gardner in his 1983 book ‘Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences’. Gardner articulated seven criteria for a behavior to be considered an intelligence. These were that the intelligences showed: potential for brain isolation by brain damage, place in evolutionary history, presence of core operations, susceptibility to encoding (symbolic expression), a distinct developmental progression, the existence of savants, prodigies and other exceptional people, and support from experimental psychology and psychometric findings.

Gardner chose eight abilities that he held to meet these criteria: musical–rhythmic, visual–spatial, verbal–linguistic, logical–mathematical, bodily–kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic. He later suggested that existential and moral intelligence may also be worthy of inclusion. Although the distinction between intelligences has been set out in great detail, Gardner opposes the idea of labeling learners to a specific intelligence. Each individual possesses a unique blend of all the intelligences. Gardner firmly maintains that his theory of multiple intelligences should ‘empower learners’, not restrict them to one modality of learning.

Communication

One-Way Communication

One-way communication uses old-fashioned methods. It:

- Imparts facts and knowledge to learners

- Does not expect serious thought, input – or challenges – from learners

- Permits occasional questions only – for clarification

Old didactic (instructional) styles of teaching are out!

Two-way communication often still relies on the educator to:

- Do most of the talking

- Impart information

Although it allows some questions and comments from learners.

Two-way communication is better, but not the best method!

Facilitated or Multi-Way Communication

Here, the educator acts as a facilitator. They guide the process, and ensure that all learners have the opportunity to contribute, and that every contribution is valued. This is the most appropriate method for humane education.

Moral Development

(Piaget's theory)

Piaget observed that the thinking of young children is characterized by egocentrism. That is that young children are unable to simultaneously take into account their own view of things with the perspective of someone else. This egocentrism leads children to project their own thoughts and wishes onto others.

Children begin in a stage of moral reasoning, characterized by a strict adherence to rules and duties, and obedience to authority. Younger children judge against predetermined rules. They value the ‘letter of the law’. For this to work, they need to understand responsibility and outcomes i.e. the imminent sanctions that will occur. This is reinforced by their authority relationship with adults.

Older children are able to determine right from wrong in a wider and more personal sense. They are even able to judge the implications of intent on an action. They value the ‘intent or principle of the law’.

Interactions with other children help to develop this higher moral reasoning – when different rules are traded and a sense of fairness derived (from balancing competing norms and approaches).

Piaget concluded from this work that schools should emphasize cooperative decision-making and problem solving, nurturing moral development by requiring students to work out common rules based on fairness. Thus, Piaget suggested that educators should provide students with opportunities for personal discovery through problem solving, rather than indoctrinating students with norms.

Moral Education

Kohlberg used moral development theories as a basis for rejecting traditional character education methods – which emphasized certain moral virtues and vices, giving learners opportunities to recognize and practice the virtues. He considered that it would prove impossible to determine which virtues were most worthy of espousal. So this approach would, he felt, lead to the educator arbitrarily imposing certain values depending upon their societal, cultural, and personal beliefs. Because of the difficulty of ethical relativity, Kohlberg believed a better approach to affecting moral behavior should focus on stages of moral development.

The goal of moral education, it then follows, is to encourage individuals to develop to the next stage of moral reasoning. This can be achieved through moral dilemmas, and including experiences for learners to act as moral agents in the community.

Teaching practice should work to distinguish morality from convention. Facilitation should be based on the assumption that there are no single, correct answers to ethical dilemmas, but that there is value in holding clear views and acting accordingly. In addition, there is a value of toleration of divergent views. It follows, then, that the teacher's role is one of discussion moderator, with the goal of teaching merely that people hold different values; the teacher does attempt to present his or her views as the ‘right’ views.

So What Methods Work?

"The mind is not a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be ignited." Plutarch, a follower of Socrates

A really good educator is not one who is standing out the front of the class dictating information to the kids. Enabling educators work out a process that will draw the most from their learners. Then they clearly set out the task and give the learners some tools. They reinforce the belief that the learners are bright and can figure things out – whilst making it clear that they are there to help, if the learners need it.

Learners are the major players in their own learning. They are not the only players – as these will include fellow learners, friends, educators, family, writers etc. To become effective humane educators, teachers need to really get to know their learners as people – on a one on one basis. They should be interested in their home lives, their emotional lives, and their personalities, skills and talents. They should also make an effort to understand the learners’ individual learning styles and learning preferences, and try to use these when giving individual support. Also, make sure that group work is arranged so learners with a range of learning styles can work together and support each other (see Kolb’s learning styles above for some suggestions on teaming learning styles that complement each other). This individual attention may be difficult in today’s large classes, but it is not impossible.

As regards catering for different learning styles, ensure that lessons are designed so as to cater for each different learning style (as every classroom will contain a range). It is tempting for an educator to design lessons according to their own learning style. Be aware of this, and guard against it! It helps to consider your own learning style, so you are aware when you are doing this.

Lessons should be well planned to break tasks down into manageable units, developing a process that unfolds and builds on learning. This is done by analyzing the task, and splitting it into segments. Make sure that the process covers all aspects of the learning cycle. Build lesson plans that include: - theories, thinking time, building concepts, task structure and rules, and active experimentation. This can be done by including homework that gives an opportunity to consider and work on theories, and practical projects and activities through which abstract information (e.g. discussion items) can be tested or developed. Opportunities to test and put learning into practice must be included.

Also, do not forget the need to include multisensory resources and the possibility for multi-sensory outputs or feedback (visual, auditory, kinesthetic).

Where learners are old enough, it is useful to carry out activities in groups. Where possible, this should include self-organization of groups (include self-selection of roles – incorporating identification of skills, talents etc. and making appropriate use of these). Learning how to cooperate in a group is a valuable skill – particularly getting along with others, the art of compromise, and using people in ways that maximize their talents.

Group work should be well organized, with clear explanations of tasks and rules. Give groups control over their environment and the ways in which they get to the required results. Self-regulation of timing and work flow is another useful aspect.

Learning is facilitated when it is based on a reality which the learner recognizes and accepts. This can be achieved through using project-based learning, or using realistic role plays and situational analyses.

With project work, it helps to get the learners excited about a goal. Then fit the learning experience around this. Learners become more enthusiastic when they are able to follow a project of their own choosing, and agree on a common goal.

Other concrete experiences that can be used to help learning would include field trips, voluntary work, drawing and building exercises, classroom productions (arts, film making, musical events, plays etc.).

Creative methods are particularly helpful, because they use the right side of the brain that provokes intuitive responses. This will help to move learners away from learned rules and approaches, which may tend to be reinforced by the factual or theoretical learning that uses the left side of the brain (that deals with information and analysis).

Another tool that can help learners to develop their creative, intuitive responses is meditation. Meditation is a skill that stills the active mind, to create a space for intuition and insights. There are various meditational techniques that can be used, and these can be tried out and the most popular used. The value of meditation is well documented – not only in creating a calmer disposition and assisting intuition, but also in improving concentration in schools. If the conventional school – or parents – are against meditation, then this can be a ‘silent time’ or a ‘peace break’. Here, learners can relax and be quiet. They should be encouraged to still their minds – perhaps assisted by quiet music, a nature visit, or simply listening to their own breathing or heartbeat.

Educators can help children to differentiate between the norms and conventions of their culture and the universal moral concerns for justice (fairness) and welfare. Five educational practices enable teachers to engage in moral education that is neither indoctrinating nor relativistic:

- Moral education should focus on issues of justice, fairness and welfare.

- Moral discussion promotes moral development when the students use ‘transactive’ discussion patterns (negotiations), are at somewhat different moral levels, and are free to disagree about the best solution to a moral dilemma.

- Effective moral education programs are integrated within the curriculum, rather than treated separately as a special program or unit.

- Cooperative goal structures promote both moral and academic growth.

Firm, fair, and flexible classroom management practices and rules contribute to students' moral growth. Teachers should respond to the harmful or unjust consequences of moral transgressions, rather than to broken rules or unfulfilled social expectations (according to Larry Nucci, Director of the Office for Studies in Moral Development and Education and Professor of Education and Psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago).

The central method used to generate moral development is moral discussion. The use of discussion acknowledges that social growth is not simply a process of learning society's rules and values, but a gradual process in which learners actively transform their understanding of morality and social convention through reflection and construction. That is, learners' growth is a function of meaning-making rather than mere compliance with externally imposed values.

Stage change occurs most readily in learners who disagree about the moral solution to a dilemma. Educators can achieve best results by selecting moral dilemmas that are likely to generate disagreement. The educator must permit a variety of opinions and attitudes, and create a classroom atmosphere where learners accept others when their attitudes, beliefs, and values differ from their own. Moral education should assist learners to move through progressively more adequate forms of resolving conflicting claims to justice or human rights.

The constructive exploration of moral dilemmas can be helped by challenging learners’ abilities. They think deeply (and ‘out of the box’) when presented with stretching moral dilemmas. But educators should not be tempted to present learners with materials that are beyond their age level, as this can dishearten and demoralize.

When facilitated effectively, humane education can help to develop ‘multiple intelligences’, which include emotional and interpersonal aspects as well as the cognitive aspects that are developed using more traditional teaching programs. It develops the skills needed to manage emotions, resolve conflict non-violently, and to take just and responsible decisions.

Classroom Management

Moral discussion is more like to take place in classrooms employing co-operative goal structures in a democratic atmosphere than in the traditional classroom environment. Schools should emphasize co-operative decision-making and problem solving, nurturing moral development by requiring students to work out common rules based on fairness. The use of reasoning to respond to transgressions also aids moral development - the morality of justice emerges from coordinating the interactions of autonomous individuals.

Classroom management should be:

- Firm

- Fair

- Flexible (with room for negotiation between educators and learners)

Educators should foster an atmosphere in the classroom that is open, respectful and tolerant. Diversity should be valued, and different abilities stressed and appreciated. Different cultures, religions, and social constructs should be explored and understood in a sensitive and supportive manner. Educators should preach and practice empathy and compassion for all, sprinkled liberally with patience and understanding!

The educator should provide students with opportunities for personal discovery through problem solving, rather than indoctrinating students with their own norms and values. Indeed, educators should work gradually to deconstruct social values and norms, whilst learners are replacing these with their own personal moral values.

Class discussions and negotiations should be encouraged. The educator should create an atmosphere which is open to all viewpoints. No views should be crushed or disregarded – even the more controversial. Create climate of trust and acceptance in class. The class should be a ‘safe haven’ in which contributions are welcomed and valued. Where learners bring forward worrying (or intolerant or antagonistic) viewpoints, ask other learners to comment. Their reflections are likely to provide a greater spur to further reflection.

The way in which feedback is approached is as important as the task itself. Negative criticism should be discouraged (as it is de-motivating). A classroom culture should be developed where appreciative responses are the norm. Concentration on using strengths in teamwork should be followed by recognition of valuable contributions. Group work can build on this, by working consistently towards ‘best fit’ – giving appropriate roles and support within the team. Pleasure and appreciation should be given for shared outcomes. As groups feed back to the complete class, applause and constructive comments should be invited (until these become the norm). Feedback is an art to be learned. Constructive criticism should always be welcomed as a learning opportunity, but the way in which this is worded is important! The educator should guide the learners into ways of giving positive feedback (including through developing empathy with the person receiving feedback).

The educator should encourage the class to care for any learners having problems with their behavior or learning. The ‘buddy’ system can be useful – where an able learner takes a struggling learner under their wing (as a friend and mentor). Always check understanding, so learners are not marginalized or left out of class activities. Fostering the morality of care is an important part of classroom management which builds interconnectedness.

Further Resources on Methodology

Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development

Synthesis of Research on Moral Development

Moral Development and Moral Education: An Overview

Learning Styles and Learning Theory