29. Effective Meetings

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

Tips on effective meetings

Method

Consider the following tips how to schedule and prepare for meetings, meet and follow-up, and try to incorporate any approaches that are suitable for your national situation.

Meeting Preparation

- Find out all you can about your target. See the following tools for guidance:

- 4. The ‘Context, Evidence, Links’ Policy Framework

- 5. Decision and Influence Mapping

- 6. Allies and Opponents Matrix Also check whether they have made any speeches/ written articles, documents on the issue.

- Decide what it is you want from this meeting – it is unlikely you will achieve all your objectives in one meeting – so choose a first step.

- Plan tactics based on what you want to achieve.

- Prepare a presentation that speaks directly to the interests and priorities of the policy-maker.

- Make a note of ’key points’ that must be made

- Agree who is going to the meeting from your side (if it is a formal meeting its best not to go alone) and who will say what.

- Be clear about what your position is and what your bottom line is. Rehearse your arguments.

- Anticipate and prepare answers to potential questions (e.g. about why they should support you, and responses to common opposition arguments).

- Prepare material to leave with decision-makers (e.g. a letter or position paper). This should briefly explain the issues and aims of the campaign clearly and concisely, and include a clear request for action.

Scheduling a Meeting

- If it is to be an informal meeting, find out their schedule so you can meet them ‘by chance’.

- If it is to be a formal meeting, they have to agree to meet you. This may involve a lengthy process of ‘phone calls, letters, or e-mails. Do not become disheartened.

- To schedule a meeting, contact the office of the policy-maker by letter, e-mail or ‘phone, or through someone with a personal connection. Explain who you are, what organization or coalition you are representing (and its size/representation), and why your issue is important and urgent enough to justify a meeting.

- If you do not receive a response to written enquiries, telephone or visit the office personally.

- If you still do not receive a response, correspond with (or meet with) an aide to make arrangements.

- Alternatively, try different approaches first e.g. meeting researchers, economists or statisticians to pave the way for a policy meeting.

- Do not be worried if you are told to meet an aide (or junior colleague) – some aides can be very influential, and you will learn important background information (that you miss if you meet directly with the policy-maker).

- Once the meeting has been agreed, clarify who will attend, how long it will last, and what the expected agenda is.

- Call about one week beforehand to confirm the meeting and the policy-makers availability.

Meetings

- Dress professionally.

- Bring business cards (and give these out at the beginning of the meeting).

- Arrive on time and establish a rapport. Ensure everyone is introduced clearly and that it is clear which organization they represent.

- Briefly present your case – do not take too long, as your target probably knows your position already.

- Always thank or praise them for constructive work on your issue.

- Every meeting will be different, but bear in mind that the meeting is about dialogue – so you need to listen to them – and watch non-verbal signals - as well as speaking (active listening will enable you to learn valuable intelligence about their position).

- Ask for more details if you don’t understand their arguments.

- Discuss the issue from the policy-maker’s perspective.

- Take and leave appropriate reports, position statements etc. briefings etc. Also papers to show popular support (e.g. copy media reports, opinion poll surveys, petition results etc., and information on coalition members).

- Remember you are not trying to win an argument; you are trying to influence them and reach agreement.

- Try to respond to their objections, but keep to your agenda – do not allow yourself to be distracted. Concentrate on your priorities and what you want them to do.

- Focus on positive solutions. Pick up on any openings or compromises they offer you.

- Above all – remain calm and pleasant.

- Avoid criticisms of past actions or inactions. Attacks can alienate and cause decision-makers to withdraw potential support for the campaign.

- If you can, take notes of everything that is said.

- Offer to provide more information (it keeps doors open).

- Make sure something is agreed before the meeting ends.

- Establish on-going dialogue e.g. a second meeting, a promise to review the issue or an agreement to attend a more in-depth workshop on the issue etc.

- At the end of the meeting, sum up what has been agreed and any action points.

- Thank them for the meeting.

Meeting Follow-Up

- Hold a debrief meeting with all members of your delegation straight afterwards.

- Review what was said and discuss the potential for further movement. Plan your next steps.

- Write up your notes and circulate them to your organization, partners/coalition members as appropriate.

- Write to the people you met, thanking them for the meeting and confirming the points covered by the meeting and what was agreed - so that the agreement is on paper (making it harder for them to back out). Re-send your summary and provide an update on the situation, if appropriate, as well.

- If you agreed to do something at the meeting do it promptly & do it well. Always provide any requested material or information. This will encourage them to do the same.

- Plan the next meeting.

If action is agreed:

- Remember to thank everyone who had anything to do with bringing about the policy change - even those who were reluctant collaborators: you may need their help again in the future.

- Suggest a coalition working group be established to monitor the implementation of the proposed change.

- Offer your organization's services to assist the person or team responsible for implementing change.

- If formal contacts are refused, still monitor implementation and maintain contact on this.

Larger Meetings

You can use similar principles for larger meetings, such as: seminars, workshops, conferences, and even public meetings. It is necessary to prepare thoroughly, target your interventions to the issue and audience, prepare brief, targeted written supporting materials, anticipate possible arguments and questions, use the principles of effective presentation and negotiation (see below), where applicable, use every opportunity to develop personal relationships when there, and follow-up appropriately. Too many advocates – and policymakers! - attend meetings, and forget about them the moment they leave the venue.

28. Managing Coalitions

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

Advice on managing coalitions

Method:

Read the following advice, and apply it whenever applicable to your work with coalitions

Tips on Managing Coalitions

- Establish a steering group to monitor implementation of the work, and make adjustments regularly.

- Create a secretariat.

- Establish a clear decision-making process that enables each coalition member to be involved. No members should be left out of key decisions.

- Establish a clear operating structure. Vertical, hierarchical structures are rarely appropriate for developing coalitions – consider a more fluid horizontal structure, based on team work and rotating responsibilities.

- It is important to define: management responsibility; how finances are raised, and resources distributed and divided; how members are expected to participate; and the consequences for members who fail to uphold their commitments to the coalition.

- For the smooth management of the coalition, there must be an apparent division of roles and responsibilities.

- The coalition should formulate a clear plan for how to achieve the advocacy campaign objectives.

- For specific tasks and activities, it might be beneficial to form subgroups. Subgroups should report back and be accountable to the larger coalition.

- When conflicts or disagreements arise, it is important to deal directly and openly with these. It is helpful to establish dispute procedures in advance (possibly including the use of a facilitator or mediator).

- Establish a clear communication system. Member organizations should be kept aware of developments and changes in the coalition on a regular basis.

- Prepare to fill expertise gaps by recruiting new members or capacity-building.

- Network to broaden the coalition’s base of support (co-operating with other coalitions, networks, or alliances or broadening the coalition or its base of support).

- Plan events incorporating credible spokespersons from different partner organizations.

- Create a member database (name, organization, type and focus of organization, contact details, etc.).

- Plan well ahead - coalition action can be cumbersome!

- When the coalition has successes, celebrate and spread the glory! (Motivation keeps coalitions going).

27. Logframe

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

A Logframe (logical framework matrix) is a project management tool that is often used in development and civil society work. It provides a practical framework for program learning and review (M&E).

The aim is to work towards agreed objectives, with any review being in this context. The framework helps to develop a results orientation, and a move away from being ‘activity-driven’ (which can lead to being ‘busy going nowhere’!).

Method:

The following framework is used to map out advocacy issue aim, objectives, indicators, outcomes and activities. It is then used as a project management tool, and for program learning and review purposes.

Logframe

Programme Area:_________________

Date:__________________

| Aim (or Goal) | |||

| Objective 1 | Indicators | Means of Verification | Risks and Assumptions |

|

|

|||

| Outcomes | Indicators | Means of Verification | Risks and Assumptions |

| 1.1 |

|

||

| 1.2 |

|

||

| 1.3 |

|

||

| Activities | Roles and Responsibilities | Timeframe/Target finishing date | |

| 1.1 |

|

||

| 1.2 |

|

||

| 1.3 |

|

||

| 1.4 |

|

||

| Objective 2 | Indicators | Means of Verification | Risks and Assumptions |

|

|

|||

| Outcomes | Indicators | Means of Verification | Risks and Assumptions |

| 2.1 |

|

||

| 2.2 |

|

||

| 2.3 |

|

||

| Activities | Roles and Responsibilities | Timeframe/Target finishing date | |

| 2.1 |

|

||

| 2.2 |

|

||

| 2.3 |

|

||

| 2.4 |

|

||

| Objective 3 | Indicators | Means of Verification | Risks and Assumptions |

|

|

|||

| Outcomes | Indicators | Means of Verification | Risks and Assumptions |

| 3.1 |

|

||

| 3.2 |

|

||

| 3.3 |

|

||

| Activities | Roles and Responsibilities | Timeframe/Target finishing date | |

| 3.1 |

|

||

| 3.2 |

|

||

| 3.3 |

|

||

| 3.4 |

|

||

Add more sections as necessary – both categories (e.g. resources/budgets) and additional objectives

The Logframe works on the following propositions:

- If these Activities are implemented, and these Assumptions hold, then these Outcomes will be delivered

- If these Outcomes are delivered, and these Assumptions hold, then the Objectives will be achieved.

- If these Objectives are achieved, and these Assumptions hold, then this aim (or aim) will be achieved.

Some people use ‘aims’ and ‘objectives’ interchangeably, but they actually denote separate and different concepts. The terms used are explained briefly below:

Aim - is an aim or purpose - the required long-term impact or program/policy goal.

Objective – is something you plan to achieve. The medium term results that the activity aims to achieve (in terms of benefit to target groups). It is more specific – and shorter term - than an aim.

Outcomes are the tangible results (changes, products or services) that the activity will deliver.

Indicators are the evidence that shows how an objective or outcome has been achieved. They should be measurable, as they provide an objective target against which progress may be measured. They should be Objectively Verifiable (OVIs), and define the performance standard required to achieve the objective. They specify the evidence we need to tell us that the overall aim, the project purpose or indeed any required outcome is reached. Activities are not verified by indicators; instead we identify the inputs needed to carry out the activities. Indicators are defined by a set of characteristics, which are described in terms of quality, quantity, location, and time. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Means of Verification (MOV) tell us where we get the evidence that the objectives have been met and where the data necessary to verify the indicator can be found.

Finally and most important, the framework is based on a set of Risks and Assumptions. Inherent in all plans are a series of risks.

Assumptions are the conditions that must exist if the project is to succeed but which are not under the direct control of the project. They are included in the log frame, if they are:

- Important for the project success

- Quite likely to occur

Assumptions influence the next higher level of achievement in the log frame, e.g., the project aim will be achieved, if the outcomes are carried out and the assumptions occur.

Formulating assumptions should lead to consideration of risk management and contingency planning needed.

Assumptions which are almost certain to occur should not be included in the log frame. Assumptions which are most likely not to occur and which can not be influenced by alternative project strategies are killer assumptions! They will jeopardise the project success. When killer assumptions occur the project must be re-planned!

The fundamental logic is therefore that if you carry out the activities explained these will result in the expected outcomes. If these outcomes are successful you should achieve your objectives. The successful accomplishment of the objectives should contribute towards successful completion of the final aim.

Outcomes/Expected Results are:

The changes in people’s behavior resulting from the completion of a set of activities that contributes to the achievement of the objective. (The outcome and activities should be negotiated and agreed with the relevant partners.) These should be monitored closely to capture learning and to enable adjustments when progress is not being made.

The Outcome/Expected Result should be the effect of the completion of a set of activities.

An activity is defined as:

The detail of what is done to achieve the outcomes and expected results which will put into practice the objectives and the associated aim.

Detailed planning needs to include the steps needed, who is responsible for each, and agreed deadlines.

26. Six Thinking Hats (de Bono)

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

This is a simple framework from Edwards de Bono which provides an alternative to the traditional Western adversarial way of thinking. This framework provides a creative and constructive way of assessing options from different perspectives, and is suitable in many different cultures.

Method:

There are six imaginary thinking hats. Only one is used at any one time. When that hat is used, everybody in the group wears that hat. Everybody is now thinking about the problem in the manner determined by the hat, so consideration goes ahead in parallel, and in a timely way without the usual divergence. The six thinking hats are:

The White Hat

The white hat indicates an exclusive focus on information. What information is available? What information is needed? How are we going to find the information we need?

Think of white paper and computer print-out.

The Red Hat

The red hat allows free expression of feelings, intuition, hunches and emotions – with no need for apology or explanation. Feelings are expressed without justification. Intuition should be given free rein, and never decried or disregarded.

Think of fire and warm.

The Yellow Hat

The yellow hat is the yellow logical, positive hat. Under the yellow hat the seeker seeks out the values and benefits. The thinker thinks out how the idea can be made workable and put into practice.

Think of sunshine and optimism.

The Green Hat

The green hat is the creative hat. Under the green hat we put forward alternatives. We seek out new ideas. We modify and change suggestions. We generate possibilities. We use movement and energy to produce new ideas.

Think of vegetartion, growth, energy, shoots, etc.

The Blue Hat

The blue hat is the control hat. The blue hat is concerned with the management of the thinking process. The conductor of an orchestra conducts the process, and gets the most out of the musicians. The ring-master in a circus makes sure that proceedings are ordered and in sequence. The blue hat is for the thinking process itself.

Think of blue as sky and overview.

The blue hat defines the issue or problem, and sets up the sequence of other hats to be used, and ensures that the rules of the six hats framework are followed.

Using the Hats

Using the six hats framework in the context of strategic choice, the blue hat can be used to consider the options at hand and to establish a process using the most useful thinking hats.

It often helps to start with a blue hat, and to end with a blue hat. But the rest of the process can be built. It is also possible to change it during the process, in order to deal with issues that arise.

25. Approaches for Effective Policy Engagement

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

This tool is a table providing suggested solutions to key obstacles encountered by NGOs/CSOs in policy engagement.

Method:

Use the table below for guidance.

| Key Obstacles for CSOs/NGOs | Potential Solutions |

| External | |

| Adverse political contexts constrain CSO policy work |

|

| Internal | |

| Limited understanding of specific policy processes, institutions and actors | Conduct rigorous context assessments. These enable a better understanding of how policy processes work, the politics affecting them and the opportunities for policy influence. |

| Weak strategies for policy engagement | Identify critical policy stages – agenda setting, formulation and/or implementation – and the engagement mechanisms that are most appropriate for each stage. |

| Inadequate use of evidence | Ensure that evidence is relevant, objective, generalizable and practical. This helps improve CSO legitimacy and credibility with policymakers. |

| Weak communication approaches in policy influence work | Engage in two-way communication and use existing tools for planning, packaging, targeting and monitoring communication efforts. Doing so will help CSOs make their interventions more accessible, digestible and timely for policy discussions. |

| Working in an isolated manner | Apply network approaches. Networks can help CSOs: bypass obstacles to consensus; assemble coalitions for change; marshal and amplify evidence; and mobilize resources |

| Limited capacity for policy influence | Engage in systemic capacity building. CSOs need a wide range of technical capacities to maximize their chances of policy influence |

Policy Engagement: How Civil Society can be More Effective Overseas Development Institute (ODI)

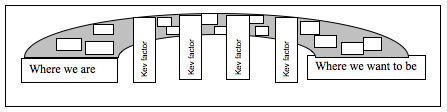

24. The Bridge

Category:

A Primary Tool

Description and Purpose:

The bridge is a visioning and planning tool that can be used to help organizations to assess where they are now, where they want to be, and how to bridge the gap.

Method:

Participants draw or list characteristics of their current situation. Then they visualize where they would like to be, and draw this (or represent it with symbols). This can be done through a guided meditation, or just through using the following useful tool:

These can then be mapped on the bridge diagram (see below).

Then, the aim is to construct a bridge between two sections, with the uprights being the key supporting/enabling factors.

An effective way of reaching this point is to begin by brainstorming all the things that need to be achieved or ‘got right’ in order to reach the right hand side of the bridge (the point where you want to be). Use ‘Post Its’, with idea on each. Make it clear that each major thing that needs to be achieved – strategies, aspirations or actions - should be included, regardless of whether it is directly related to the advocacy campaign (e.g. funding, staffing etc.).

When this process has finished, group the ideas into pillars (or columns) of similar themes. These will then represent the key themes that need to be tackled to reach the desired end point. This constructs a bridge between the two stages.

Be sensitive to the group dynamic, and guard against domination. People of lower status may be unwilling to challenge the status quo regarding the current state of the organization, decisions regarding the future and how to get there.

The benefits of this tool are that it:

- Builds a common vision and sense of purpose.

- Helps local and external people to better understand their aims and potential contributions.

- Lends structure to analysis and planning

23. Risk Analysis

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

This is a tool for carrying out a risk analysis on your strategy or action plan.

Method:

Preparation:

Provide participants in advance with copies of your draft strategy or action plan, and any important documents about your external environment (e.g. PESTLE), internal organization (e.g. SWOT) and the plans of your opponents and competitors.

Ask them to examine your draft strategy or action plan and consider any potential risks or threats (using both the documentation and their own knowledge and experience).

Meeting:

As a group, brainstorm any risks or threats that could jeopardize your plan using ‘Post It’ slips.

Then, group and categorize these – first according to whether they are ‘internal’ or ‘external’ risks. Then discuss what steps you could take to mitigate the risks, either by changing your plan or integrating the risks into this plan. Agree in the full meeting any serious risks that would mean your plan needs to be changed.

Next, break into two groups – one to consider ‘internal’ risks and one to consider ‘external’ risks. Each group should be asked to group and categorize the risks, entering them on the table below, together with their thoughts on the action to be taken to mitigate these risks.

Then, each group should report back to the main meeting with its recommendations. The other group should then critique their analysis and suggestions, and add any agreed changes.

| Risks Possible threat |

Probability Likelihood of occurring (1=low, 5=high) |

Importance (1=low, 5=high) |

Total Risk Level (importance x likelihood) |

Mitigation Steps to mitigate |

| Internal risks | ||||

| External risks |

22. Audience Analysis

Category:

Recommended

Description and Purpose:

This tool maps is designed to assist analysis into advocacy audiences in order to target messages more effectively.

Method:

Map out advocacy audiences using the following chart as a guide. If necessary carry out any further research needed before completion. Then, assess the most effective way in which to target messages to each audience.

Advocacy Objective:

| Audience | ||

| Audience knowledge about issue/objective | ||

| Audience openness to issue/objective | ||

| Issues priorities of the audience | ||

| Audience classification (Ally/Undecided/Opponent) | ||

| Further research required on the audience? | ||

| How to target messages |

Adapted from SARA manual

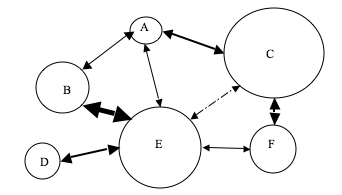

21. Systems Mapping of Targets

Category:

Optional

Description and Purpose:

A systems map is a ‘rich picture’ that is drawn up to show the relative power and relationships between different bodies. It can be used to chart and analyze the power relationships between the key players in an organization, including potential targets (primary and secondary).

Method:

To draw a systems map, you use circles to represent each player, using different sized circles to depict the relative power of each. Then they are linked using connector arrows, which are also different sizes to depict the relative strength of the relationships between them. This is an example:

One aspect to remember is that for any particular policy decision there is always one decision maker (or decision gatekeeper), even if there may be many decision approvers and decision advisers within the organization. The decision maker is the person responsible for that policy or issue. They may not have sole authority, but the policy will not go forward for approval without their agreement. In government, the decision maker is often a minister. Decision approvers have a formal role in approving proposals presented to them. In a government, that may be the Cabinet, The President and/or the Parliament depending on the system of government in operation and the issue concerned. In a company, approvers may be the Board of Directors.

Decision advisors may be junior staff or civil servants, and there will also be a number of internal stakeholders who want to influence that decision (through formal and informal means). This is in addition to external stakeholders, including ourselves, who also want to influence that decision.

20. Involvement of Grassroots Groups

Category

A Primary Tool

Description and Purpose:

This is a tool for analyzing the most appropriate approach to the involvement of grassroots groups in your advocacy work. It works by considering the pros and cons of the three options as a basis for discussion and decision-making.

Method

The three approaches to be considered are:

- Leading grassroots groups

- Representing grassroots groups

- Working with grassroots groups

Exercise:

Take a few minutes to think of some of the pros and cons of each approach and make some notes in the table below:

| |

Leading | Representing | With |

| Pros | |

||

| Cons |

How you see advocacy in this dimension will depend to an extent on how you see the role of grassroots groups. There is not one correct approach – each has its own advantages and disadvantages.

If you have a greater level of knowledge, skills and resources than grassroots groups, then leading advocacy for them can be quicker and more efficient. You could even advocate in your own right. There may be a short-term advantage in leading them if you want to add weight to your own advocacy, without changing your strategy (or taking time to capacity build).

Representing their positions in advocacy may require much preliminary education and awareness – and giving yourself over as a platform for their views.

Advocacy with grassroots groups gives a more level platform for advocacy work. However, it is not as simple as it sounds, and the reality is often not what is claimed. For it to be genuine, grassroots groups should be involved in choosing the issue, setting the objectives and deciding on the strategy, as well as sharing responsibility for putting the strategy into practice. To be successful this requires capacity building and increased understanding of the issues and political processes.